FROM ANGLO-SAXON POETRY

TO MODERN CINEMA

Ana Rita Martins

e

Andreia Brito

When we had the opportunity to participate in the Avanca International Conference Cinema, our research topic, the medieval epic poem, Beowulf, was a natural choice for our presentation and essay. As researchers in medieval English literature, Beowulf stands as one of the most important and interesting manuscripts produced during the Middle Ages. Even though this poem has been a target of several studies and numerous articles and books, it was (is) our belief that much can still be said about this work and even more on its various adaptations to cinema. In fact, although Beowulf has been a focus of intensive study, its on-screen adaptations have drawn less notice. In addition, the idea of researching concepts of monstrosity from both the medieval period and today, by comparing the monsters (namely Grendel) depicted in the poem with the ones in the films, was very alluring. Indeed, it seems that monstrosity or abnormality can simultaneously fascinate and repulse us, which was a point this paper also aimed at exploring. Faced with the impossibility of focusing on all three monsters of the poem, “Beowulf at the Movies” bestows special attention to Grendel, the most human of the monsters.

As a result, as a second part of this research, it is our goal to further explore the role played by the remaining monsters of Beowulf, Grendel’s mother and the dragon, how they have been visually represented and in what ways these characters have changed in modern adaptations. Therefore, this study would be divided into three parts, each dedicated to a different monster. Another point of interest would be to look at the figure of the hero, Beowulf himself, and compare him with the later chivalric heroes such as the ones we can find, for instance, in Arthurian literature – a topic that is merely hinted at in one of the footnotes of the current paper.

For future work, we are considering different projects. On the one hand, continuing the research started in “Beowulf at the Movies”, we would like to present another paper dedicated to the hero’s adventures, but focusing only on one film that was not explored in this first paper; that is, The 13th Warrior (1999). This film is interesting for many reasons but it is especially so because the first Beowulf (or Buliwyf) is not the main character, and the second Grendel is not only a character but represents a whole people, the “Wendol”, man-eating fiends who come with the mist and invoke the “fire dragon”. On the other hand, it is also our intention to look at representations of death in early and late medieval literature. It would be fascinating to explore the way the image of death has changed from when it was faced as a natural phenomenon and part of the natural order of life to the period when death became the central figure of every thought. In fact, the Bubonic Plague changed the way the end of life was perceived which led several artists to focus their works on trying to give death a face and a body, along with everyday gestures. As the notion of monster and monstrosity has changed, so has the notion of death and it would be interesting to explore how these two ideas can mingle and be linked.

Abstract

Hwæt! (Listen!)

The feats of Geatish hero Beowulf in days gone by are well-known to modern audiences. His fight with man-eating Grendel is epic as is his battle with the monster’s mother and the terrifying dragon. During the 20th and the 21st century, the Anglo-Saxon poem Beowulf (by an unknown author) has been a source of interest and debate among academics from different fields. This paper will aim at analyzing the idea of the medieval monster.

As a starting point, concepts of monstrosity will be looked at as well as the features that define a monster both in the Middle Ages and today. Grendel is the main point of interest for this study as it considers how these ideas are reflected within this character. To do so, “Beowulf at the Movies” also analyzes the description of Grendel both in the Old English poem and in three selected movies. Are there differences between the character’s portrayal in the poem and the cinematic adaptations? To what extent has cinema reinvented monstrosity in Beowulf? How does this reflect our modern day view of humanity or the beast within?

To answer the preceding questions, this paper will focus on three main movies: Beowulf (1998) by Yuri Kulakov, Beowulf and Grendel (2005) by Sturla Gunnarsson and Beowulf (2007) by director Robert Zemeckis. These adaptations are of interest for they shed a new light on Beowulf’s monster, Grendel, and its hero. Other relevant works will also be taken in consideration as well as cultural and historical factors.

Keywords: Monsters, Middle Ages, Movies, Poetry, Heroes.

I – Monsters: Concepts and Definitions – What are we talking about when we talk about monsters?

“Everyone has the potential to become monstrous.” (Asma, 2009: 8)

When one first thinks about monsters, images of horrible and often disfigured or abnormal creatures come to mind. On a more careful consideration, one might also imagine apparently normal human beings whose inner wickedness or lack of a sense of right and wrong make them just as frightening. Either way, Humankind’s most natural response may well be to shudder and run in the opposite direction; however, the contrary might also occur.

Monsters seem to simultaneously allure and repulse us – they shake our certainties and make us wonder about our own humanity. The monster is often an aberration or a freak in order to induce the belief that a normal human existence is needed. Consequently, to a certain extent, monsters reflect that which is opposed to conventional human society. According to José Gil, in Monstros, monsters oppose the world as a place where humanity lives and feels safe in, “O mundo dos monstros não é nem a barbárie nem o inferno, não se opõe a uma ou outra representação particular, mas ao próprio mundo como imagem do local de habitação do homem racional e mortal, e do qual ele se mostra ser o mais seguro guarda” (Gil, 2006: 56)1. At the same time, by leading one to question the very limits of Mankind, monsters allow Man to ponder and have a greater understanding of their own humanity, “Provavelmente, o homem só produz monstros por uma única razão: poder pensar a sua própria humanidade” (Gil, 2006: 53)2. The term monster itself, though, is considered by most scholars to have derived from the Latin “monstrum” or “monstrare” which translates as “to show”, the question would be “what?”; what do monsters show?

According to some researchers “monstrare” is not “to show” in its most literal meaning, i.e. to show or display an object, but to teach a kind of behavior, to illustrate the best path to follow. Monsters might also be said to exist in order to “show” Man what they could be or might still become, reflecting our worst features or fears. In addition, some also state that the word “monstrum” is connected to the root “monere” which is “to warn”. Assuming these ideas are correct, one might suppose that monsters, especially throughout the Middle Ages, were both meant to point out how people should conduct themselves and function as a warning against some future misfortune. In On Monsters, Stephen Asma claims:

“Monster derives from the Latin word monstrum, which in turn derives from the root monere (to warn). To be a monster is to be an omen. Sometimes the monster is a display of God’s wrath, a portent of the future, a symbol of moral virtue or vice, or an accident of nature” (Asma, 2009: 13).

The connection between monsters and religion is indeed of crucial importance to understand their role in culture throughout the centuries. As a matter of fact, before Christianity, in the ancient polytheistic world, monsters, often children of gods or goddesses, were free agents whose divine ancestry allowed them to roam the Earth3. In Nordic mythology, Scandinavian monsters are used to show the inevitability of death. However, as the Christian religion became more and more rooted into European culture and thought, monsters had to be brought under the omnipotent God, creator of all life. A doubt then emerged, if God created all life, why did he also conceive monsters?

On the one hand, a popular theory contends God created evil, Satan and, consequently, monsters to serve a greater purpose – to punish those who somehow displeased or acted against his commandments. The monsters of the Bible, such as Behemoth and Leviathan4, do not actually plan against God or Mankind, but exist to prove the Lord’s power, becoming a more terrifying and chaotic visage of God. Hence, in the medieval period, biblical monsters served to inspire wonder, legitimize authority and encourage a fear-based morality; they were reflections of God’s power and anger. Indeed, during the Middle Ages, God, because he is unknowable and capable of stunning violence, was possibly the most fearful entity of people’s imagination. On the other hand, though, some theologians, such as St. Augustine, propose monsters exist to exceed human limits and fail in doing so, “The point of being a giant [or a monster], then, is to overreach and fail, and in that failure highlight their corruption to others as a cautionary tale and consolation” (Asma, 2009: 76). Stephen Asma once again recalls that monsters are regarded as a warning, proving, like St. Augustine suggested, that neither beauty nor size or strength are of prime importance to the wise whose sanctity lies in spiritual blessings, and not in physical ones. Monsters might also be regarded as a driving force, compelling men to surpass their own limits and, like Asma states, an excuse for doing the things they were built by nature to do: fight, protect, seize and, eventually, take on the role of champions or heroes5. Finally, one must not forget that ogres, giants, freaks, etc., may well simply fulfill the role of the enemies of God and have often done so. J.R.R. Tolkien, in his world-renowned article “The Monsters and The Critics”, stated:

“For the monsters do not depart, whether the gods go or come. A Christian was (and is) still like his forefathers a mortal hemmed in a hostile world. The monsters remained the enemies of mankind, the infantry of the old war, and became inevitably the enemies of the one God (…)” (Tolkien, 1958: 22).

There are, however, different species of monsters. To begin with, most authors distinguish the fabulous (or mythological) races which include beasts resulting from the combination of different animals, such as griffins (with the body of a lion and the head and wings of an eagle). During the medieval period, these races were considered to live at the world’s end, separated from Mankind. Opposing them, there are teratological monsters, creatures who, albeit human in origin, suffer from severe physical deformation that can be either excessive, such as having three arms, or absent, like lacking an organ. These monsters are also frequently related to monstrous births and are not qualified as a race, but as single individuals who, because of their bodily distortion, became symbols of misfortune or announcers of God’s will – they are omens.

Nowadays, fabulous races live mostly in children’s imagination, in fantasy novels or in sci-fi films6, while the so-called teratological monsters are no longer regarded as signs of the divine, but only people with physical deficiencies that might, through medical assistance, be treated and even cured. Indeed, modern writers, film directors and audiences alike have been directed to a fairly new (or perhaps one of the oldest) kind of monsters, the one whose evilness comes from within, thus displaying what we shall call “inner monstrosity.”

Inner monstrosity refers to human beings whose actions can be considered atrocious, immoral and/or evil; these acts can be murder, rape, arson, etc. – monstrous actions. According to Asma, “An action or a person is monstrous when it cannot be processed by our rationality, and also when we cannot readily relate to the emotional range involved” (Asma, 2009: 10). These “monsters” are physically normal, lacking outward features that would make them standout in an everyday crowd. Nevertheless, by committing horrific acts, men and women can be said to somehow relinquish their humanity which, today, is considered to be of much more importance to being “human”. From this viewpoint, anyone has the potential to become monstrous – perhaps not in the sense conceived throughout the Middle Ages, but, using a modern perspective, even a hero can have monstrous characteristics and if so, how can we identify or understand monstrosity?7

In the poem Beowulf, the distinction between monster and hero and whether or not monsters can have human features while heroes might commit atrocious deeds has been under the spotlight, especially in motion pictures. Opposing the medieval view of the hero and his monstrous foes, numerous modern adaptations have questioned if Beowulf was(is) truly the champion he has been considered to be or simply another kind of brute. The same is valid for his opponents, in particular Grendel, whose humanity seems to have become a major point of focus for modern authors and film directors. This paper will, thus, aim to consider how the previously mentioned concepts of monstrosity are reflected in the character of Grendel. To do so, an analysis of Grendel’s description in both the poem, Beowulf, and in three selected films will be made. Are there differences between the character’s portrayal in the poem and the motion pictures’ adaptations? To what extent has cinema reinvented monstrosity in Beowulf? How does this reflect our modern day view of humanity or the beast within?

II – Beowulf: From Poem to Film

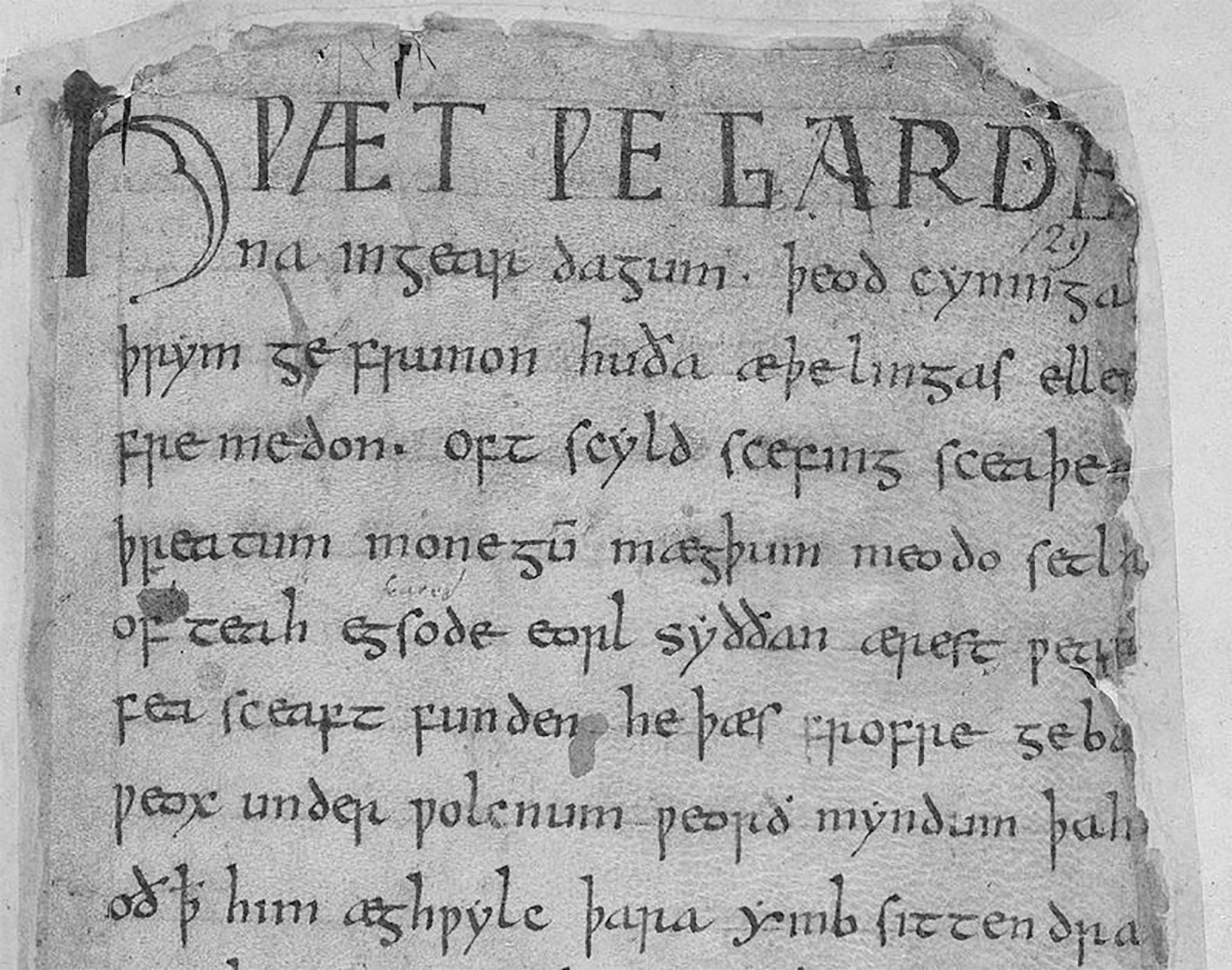

The anonymous poem, Beowulf8 is believed to have been written at some point between the 7th and the 10th century. Consisting of more than three thousand lines, this work is regarded as one of the most important pieces of English literature even though “the events it describes are set in Scandinavia” (Heaney, 2001: ix). The poem’s plotline seems simple enough, relating the feats of Geatish hero, Beowulf, and his encounter with three chief monsters, Grendel, Grendel’s mother and the dragon9. The narrative is divided into two parts: the first half is related to Beowulf’s journey to Hrothgar’s realm and return to Geatland, which represents the days of the hero’s youth, while the second portrays the champion turned king as an old man whose nation is laid to waste by a mighty and vile dragon. For the purpose of this paper, special emphasis will be given to the initial half of the poem, namely to Grendel’s role, the most human of the monsters.

When the poem begins the audience is introduced to a prosperous realm and its great king, Hrothgar, who, through his might and good fortune in war, has built a grand mead-hall, “the hall of halls” (Beowulf: line 78)10 – Heorot. Heorot is presented as an Eden, a place where the finest warriors can meet, seek shelter and receive abundant gifts for their feats in battle. However, the joy of men seems to provoke grievance and anger in Grendel who is referred to as a “powerful demon or spirit” – “ellen-gǣst”11:

Then a powerful demon, a prowler through the dark,

nursed a hard grievance. It harrowed him

to hear the din of the loud banquet

every day in the hall, the harp being struck

and the clear song of a skilled poet

telling with mastery of man’s beginnings

how the Almighty had made the earth

(Beowulf: lines 86-92).

So, why does Grendel attack Heorot? A possible explanation is related to the song about God’s conception of the world which is what seems to set off Grendel’s hate towards Heorot and its inhabitants, against whom he will inflict “constant cruelties” (Beowulf: line 165) and wage “his lonely war” (Beowulf: line 164). Moreover, some researchers have suggested that Grendel’s aversion for the song of creation might be related to his own origin since he is pronounced to be a descendant of Cain12, he “(…) had dwelt for a time / in misery among the banished monsters, / Cain’s clan, whom the Creator had outlawed / and condemned as outcasts” (Beowulf: lines 104-107). As part of the kin of Cain, Grendel is an accursed being, a monstrous exile that dwells far from human habitation. Therefore, Grendel’s evilness is somewhat explained by his ancestry – he is wicked because he descends from Cain13. Stephen Asma supports this idea stating: “The monster Grendel (…) is described as the “kin of Cain,” underscoring the medieval tendency to tether monsters to an already established hereditary line of evil” (Asma, 2009: 95).

In fact, the description of Grendel’s (and his mother’s) mere has often been compared to that of hell, combining a number of natural elements (fire, burning water, tree-roots, mist, etc.) which seem to suit the abode of a devilish creature; as Hrothgar puts it, “That is no good place” (Beowulf: line 1372). Nevertheless, if one accepts this theory, it would also be possible to claim that Grendel and his mother cannot be blamed for being enemies of God and the Christian faith, since it is only in their nature to be so. By cursing Cain, God cursed a part of Mankind that, thus, has no other choice but to be outcast. Perhaps for this reason, Grendel is often described in negative terms; he is, among others, “the demon”14, ahlæcan (verse 646) - A word also used under the graphic form āglǣca in verse 592, for instance; “the murderous visitor”, cweal-cuman (verse 792), referred to as “the caller” in Heaney’s translation; “God-cursed brute”, Wiht unhǣlo (verse 121); “the alien spirit”, ellor-gāst (verse 806); and “the one who destroys with the mouth”, muð-bonan (verse 2079), translated as “mouth” by Seamus Heaney. This last expression is a very important one because it is clearly related to Grendel’s cannibalistic feasting which, since there are numerous biblical prohibitions against the drinking of blood, must have sounded like a great offence to those who heard the story throughout the Middle Ages – another feature that would make Grendel a monster to medieval audiences, and, most likely, to modern ones as well. In the poem, although Grendel never attacks the king, Hrothgar, directly; he strikes Heorot, taking men from their beds and butchering them:

So, after nightfall, Grendel set out

for the lofty house, to see the Ring-Danes

were settling into it after their drink,

and there he came upon them, a company of the best

asleep from their feasting, insensible to pain

and human sorrow. Suddenly then

the God-cursed brute was creating havoc:

greedy and grim, he grabbed thirty men

from their resting place and rushed to his lair, (…)

(Beowulf: lines 115-123).

Interestingly, Grendel’s characteristics foretell the ones which will later be linked to the Devil. Furthermore, his connection to evil forces is continuous, a fact that may also help explain why he hates humanity and is associated to the night (he only attacks after the sunset). Nevertheless, despite all the aforementioned characteristics, Grendel is the most human-like of Beowulf’s monstrous opponents. In fact, he is depicted as a sentient being with plans and emotions of his own. In Grendel’s final attack on Heorot, one is continuously made aware of his feelings, he is “spurned and joyless” (line 720), “his rage boiled over” (line 723), and is “maddening for blood” (line 724). While it might be difficult to understand the idea of being “maddening for blood”, rage and anger are human emotions, and the fact is that everyone has felt them at one time or another. By evoking such feelings, the poet leads his listeners (or readers) to sympathize with the monster whose exile seems to be imposed by circumstances out of his control. Indeed, modern audiences have tended to feel sorry for Grendel because his wickedness has begun to be regarded as a result of being an outcast. Finally, when fighting Beowulf, Grendel becomes “desperate to flee” (line 754) and “Every bone in his body / quailed and recoiled” (lines 752-753) – the monster experiences fear, possibly one of the most common human experiences. In addition, Grendel is described as having the appearance of a man of gigantic proportions, evoking the Scandinavian tradition of the troll:

(…) One of these things,

as far as anyone ever can discern,

looks like a woman; the other, warped

in the shape of a man, moves beyond the pale

bigger than any man, an unnatural birth

called Grendel by country people

in former days. They are fatherless creatures

(Beowulf: lines 1349-1355).

So Grendel not only shares human emotions, but also has a human-like visage. Besides his actions, his size and strength seem to set him aside from Mankind, however cannot the same be said about Beowulf? The champion from Geatland is often portrayed as chief amongst men, “There was no one else like him alive. / In his day, he was the mightiest man on earth, / high-born and powerful. (…)” (Beowulf: lines 196-198); as strong as thirty men and capable of beyond human prowess, Beowulf possesses features that might also be considered monstrous in appearance. In Pride and Prodigies, Andy Orchard claims Beowulf fights monsters because only then is he well-matched since, when facing human opponents, his methods, too, are inhuman. Maybe this is why when Grendel and Beowulf meet, their fight becomes blurry – it is difficult to distinguish the two adversaries whose heart seems to be filled by hate. Moreover, Beowulf is described as “desolate and alone” (line 2368), a feeling that Grendel, as an exile, must certainly share.

According to Andy Orchard:

“Grendel and Beowulf meet in an atmosphere in which the distinctions between man and monster have been deliberately obscured, and in a twilight domain where the mark of the assailant is measured as much in terror and anger as in corporeal harm” (Orchard, 2003: 37).

As hero and monster are tangled by the darkness of the night, both characters became increasingly linked by their larger than human physique and fury. Beowulf awaits Grendel “in a fighting mood” (line 709) while Heorot’s door collapses at Grendel’s touch because “his rage boiled over” (line 723). Finally, both characters are also connected by the word āglǣcan which means “demon”, “monster”, “fiend”, and “wretch”. In the poem’s account of Beowulf’s descent into Grendel’s mother’s monster-mere, the poet uses this term ambiguously to designate the monsters and Beowulf himself (verse1512). Nevertheless, it is clear that Grendel’s days of terror and mayhem are coming to an end. Clenched by Beowulf’s powerful armlock, Grendel’s arm is torn out of its socket, causing the creature’s death:

The monster’s whole

body was in pain, a tremendous wound

appeared on his shoulder. Sinews split

and the bone-lappings burst. Beowulf was granted

the glory of winning; Grendel was driven

under the fen-banks, fatally hurt,

to his desolate lair. His days were numbered,

(Beowulf: lines 814-820).

Not much further information is provided about Grendel, only that he dived deep into the marsh and, then, to hell – ostensibly the right place for a creature of the darkness and a heathen, on top of that. The trials on Heorot, though, are far from ending and soon another creature of the night comes to Hrothgar’s mead-hall seeking revenge, Grendel’s mother.

Like her son, Grendel’s mother, who remains nameless throughout the story, has devilish features; she is described as a “monstrous hell-bride” – “āglǣc-wīf” (verse 1259). However, her reasons for attacking the Danes are clear, she wishes to avenge her dead son by killing whomever she can lay her hold on. Unlike what happens with Grendel, the audience, medieval or modern, can easily relate to such grief and want (or need) to even the score, making this she-creature much more sympathetic. In the end, though, she too is defeated by Beowulf who swims into her underwater lair and manages to end her life. Interestingly, the level of difficulty increases with each battle so while Grendel causes few problems, his mother, apparently less strong, almost succeeds in killing Beowulf. Grendel’s mother also plays a key role in constructing her son’s monstrosity for, during the medieval period, it was believed that the birth of monsters was a direct result of maternal perversity. In fact, if the mother was immoral or somehow committed blasphemous acts, which might include simply looking at a painting, then the child would naturally be a monster or a freak. José Gil comments that, up until the 18th century, a direct connection between monstrous births and female perverseness was commonly made:

Toda uma tradição que vai até ao século XVIII associa o nascimento dos monstros à «podridão» matricial. Existe uma relação muito directa entre os nascimentos monstruosos, a devassidão do embrião feminino e esse primeiro alimento visceral do embrião humano, relação que poderia ser resumida da seguinte maneira: a devassidão é uma das causas da existência dos monstros, acrescentando uma carga metafórica, como «sujidade moral», à «sujidade matricial» que alimenta o embrião. E isso provoca o nascimento do monstro. (Gil, 2006: 85).15

Furthermore, Grendel has no known father. He is, as previously mentioned, a “fatherless creature” (line 1355) which only seems to add to his mother’s own fault.

In conclusion, the poem allows for two very different readings of the same character. On the one hand, Grendel is clearly introduced as an evil monster, capable of horrific actions and descending from a line of cursed creatures. Besides the simple act of killing and maiming humans, he is the terrible being that drinks blood and eats the flesh of his victims. However, on the other hand, Grendel may also be understood as one cursed for something he did not do, therefore, having no choice but to fulfil the monstrous role he has been given by fate and God himself.

In most modern adaptations of the poem Beowulf, on screen or otherwise, this later view has been generally embraced reflecting a change in audience’s perception of what monstrosity is and, at the same time, a continuous questioning of what truly makes a monster villainous and a champion heroic. While having in mind the questions this paper was set to answer, three films were selected; they are: Beowulf (1998) by Yuri Kulakov, Beowulf and Grendel (2005) by Sturla Gunnarsson and Beowulf (2007) by director Robert Zemeckis.

III – Beowulf @ the Movies

Unlike several other medieval poems, Beowulf only started being depicted on screen in the later part of the 20th century. Nevertheless, in the last two decades this epic work of fiction has been adapted to films a number of times16, revealing a growing interest in Beowulf’s tale of heroism. Each version, though, provides a different view on the characters and settings of the Geatish hero’s adventures as well as on his opponents. For the purpose of this paper, the movies Beowulf (1998), Beowulf and Grendel (2005) and Beowulf (2007) were chosen because they stand out among the most recent adaptations due to their portrayal of Grendel, all of them showing a different perspective on a centuries-old character.

Starting with the earliest version directed in 1998 by Yuri Kulakov, Beowulf17 is an animated film in which Grendel is depicted as a monster of indistinct features that lives in the swamps near Heorot, the great hall of Hrothgar, the Mighty. Indeed, one of the most interesting points of this version of the poem lies in Grendel’s rather formless shape. Seemingly made of water, an aspect liable to be related to the fact that Grendel and his mother were supposed to be part of a mythical giant race which survived The Great Flood, the monster is a mass of indistinct matter, invincible because he cannot be harmed by mortal weapons (just like in the original poem). In this adaptation, Grendel’s invulnerability is understandable for what weapon can cut through water? Only when Beowulf, “chief among men”, grabs Grendel’s arm (his most distinguishable trait) is he able to defeat the creature. The fight scene between the two is of great interest for it looks like, while Beowulf runs to tackle the monster, he actually enters Grendel’s body and falls into liquid material. At first, the champion seems about to be defeated by the watery insides of his opponent, trapped by his long arm that squeezes Beowulf in a mighty embrace before, finally, he grips the monster’s upper limb, ripping it off and, thus, killing him.

Grendel’s wicked nature, though, goes far beyond his most unnatural appearance. In the beginning of the movie, a fisherman sets off to warn the king of the imminent arrival of Grendel, stating that “terror is coming.” In spite of this, he is ignored by Hrothgar and his men who “freely (…) feasted, fed well as each night fell, forgot all troubles [and] no tales of terror or warning did they heed.” Grendel is then described as “a creature [that] dwells in darkness who hates the smell of human happiness”, but no explanation is provided as to why. Why can Grendel not “rest until it racked this gladness”? Apparently the fact that he is a cruel monster with some type of aversion to the scent of human happiness is answer enough for this question, since no other reason is given for his assaults. In fact, it is not even made clear whether or not he attacks because he hears the song of creation like in the poem or even if his behavior has anything to do with God’s curse.

In this film, Grendel is completely disconnected from possible human characteristics, first due to his appearance, but above all because of his cruel temperament. Thus, Beowulf (1998) shows a brutal being that does not remotely resemble Man and inspires fear and disgust. From a modern perspective, one can say that there are some parts of the poem that humanize the creature. (for instance, during the fight with Beowulf and when Grendel goes back to the “demon’s mere” – line 845). Nevertheless, in this movie, Grendel is depicted as a monstrous fiend unable to relate himself to anyone and so the above interpretation must be abandoned. On the opposite corner, Sturla Gunnarsson’s version of the poem, Beowulf and Grendel18 , offers a more humane perspective of both the monster and the hero.

Produced in 2005, Beowulf and Grendel is, of the three selected movies, the one that further distances itself from the poem, introducing new characters and adding whole sequences of events to the main story. The film begins with the prologue “Hate is born” in which one watches as Hrothgar (then only a warrior) and a group of men chase after two trolls, infant Grendel and his father. Taking little time in killing the father simply because of his nature and for stealing a fish, Hrothgar sees a child (Grendel) hidden by the mountain cliff, but is unable to hurt him. This altogether modern introduction is of crucial importance in the film for it sets the action and seeks to justify why Grendel, as an adult, attacks the Danish community, but not Hrothgar. Indeed, by first making him the target of the Danes cruelty, Gunnarsson is successful in placing Grendel in the role of the victim of a horrendous crime – watching one’s parent being murdered. Stephen Asma supports this reading of the film and claims, “The blame for Grendel’s violence is shifted to the human, who sinned against him [Grendel] earlier and brought the vengeance upon themselves” (Asma, 2009: 100). Grendel’s father’s death then becomes a catalyzing moment that will set off his anger against the mead-hall and its dwellers – the place where Hrothgar’s greatest warriors were meant to be resting in soon turns into their grave, driving the king insane. In addition, although he does not speak an intelligible language (only the witch Selma19 seems to understand him), Grendel physically resembles a man of enormous proportions and overgrown body hair. As a result, the audience is lead to sympathize with the “monster” of the story that, after all, is closer to an overgrown child-like creature than a horrific man-eating troll. In fact, it is not even clear whether or not Grendel eats human flesh since such act is never actually shown. The film Beowulf and Grendel, thus, stands out from the remaining adaptations due to how it humanizes the characters involved in the story, including its champion Beowulf.

Initially, Beowulf is depicted as a rather violent warrior of extraordinary prowess; however, when he arrives to Hrothgar’s land, he reveals himself to be an intelligent man and, even though he cannot initially understand why Grendel will not fight him, he quickly realizes something is wrong with the king’s tale:

Beowulf: Has this thing, this troll, killed any children?

Hrothgar: No

Beowulf: Women? Old men?

Hrothgar shakes his head.

Hrothgar: They say that he fights with a clean-heart. He kills the strongest first. He shows us he can kill the strongest. Who cares if he spares the children?

According to Hrothgar himself, Grendel fights with “a clean-heart” which suggests the monarch knows that the real reason behind the attacks is not “hate for the mead-hall”. Nonetheless, when confronted by Beowulf, Hrothgar angrily states, “Oh, Beowulf, it’s a fucking troll. Maybe someone looked at it the wrong way.” As the story progresses, the Geatish champion (and the film’s audience) grows aware of the injustices laid upon Grendel and one might even consider that Beowulf does not intentionally kill his opponent. Actually, Sturla Gunnarsson’s vision of Grendel and Beowulf’s battle is somewhat peculiar, especially because a) the champion prevails, not through physical prowess, but by outsmarting and leading the troll into a trap20; and b) Grendel is the one who actually cuts off his own arm, effectively choosing death over being taken alive by Beowulf. Moreover, while Grendel remains dangling from the trap and begins slashing his arm, it becomes obvious that Beowulf is disturbed by such sight and pities his opponent who he comes to see not as a monster, but a man. In the end, Beowulf acknowledges, “The troll didn’t give a shit about us. Not ‘till we wronged him. He killed one, he could have killed more. He killed the one he held in blame.” Consequently, Grendel does not seek to destroy gladness, nor does he “hate the smell of human happiness” – he only takes his revenge upon those who somehow abused him first, an idea that directly contradicts the 1998 and 2007 movie adaptations entitled Beowulf21.

One of the latest cinema versions of the poem, the movie Beowulf directed by Robert Zemeckis also introduces a number of dramatic changes to the original story. Among others, Grendel is turned into Hrothgar’s son – it is the price which was paid for the sexual encounter the king had with Grendel’s mother, “Queen Wealthow: The demon is my husband’s shame.” In this adaptation, Grendel appears to be a disfigured man-shaped creature with gigantic proportions and a body covered in fish scales, possibly due to his watery descent. In addition, some malformations are visible in his body, like muscles sticking out of the skin, a jaw out of place and a very sensible ear. Similarly to what happens in the poem, the film begins with the sounds of cheerfulness, laughter and merriment coming from inside Heorot. Intriguingly, the monster strikes because he does not seem to be able to bear the loud sounds coming from the mead-hall, being extremely sensitive to high-pitched noises – a characteristic not mentioned anywhere else. This last feature is the reason why the creature attacks Heorot and its inhabitants. Like in the poem, it is a song that startles the monster and begins a massacre. After the first assault, Grendel says to his mother that Man makes too much noise. If one considers the 1998 version in which Grendel hates the smell of human happiness, this more recent adaptation relies upon a similar concept, but here he cannot bear the sounds of joy or cheerfulness. Bigger than any warrior at Hrothgar’s court, Grendel soon goes into the mead-hall again and quickly dispatches the king’s heroes. Unable to fight the terror brought about by Grendel, Hrothgar is in need of a super-human champion that can even the monster’s strength and power – that is Beowulf.

The extra-ordinary Beowulf is larger, sturdier and, one might say, fiercer than most men, which points to the idea that monster and hero are not so different after all. Indeed, the similarity between both characters lingers over the first half of the movie and their fight is, like in the poem, rather blurry, full of shadows and darkened angles. Beowulf and Grendel meet as equals, neither of which using any kind of blade or man-made weapon.

Again, however, Beowulf is able to defeat his enemy because of his intelligence – he perceives Grendel is extremely sensitive to sounds and uses this weakness to gain an advantage that will prove fatal to the monster. Once debilitated by the champion, Grendel becomes scared and attempts to run from the mead-hall to save his life, but, alas, is it too late. Similarly to what happens in Beowulf and Grendel, the Geat, after some struggle, is able to trap Grendel’s arm with a chain and, then, essentially pulls the upper limb out of his body, leading to the creature’s death.

Opposing Gunnarsson’s view of the hero, though, Zemeckis’ Beowulf comes across as an arrogant, boastful warrior with little concern about the origins or motives his uncanny opponent might have. In fact, the champion seems willing to do just about anything to achieve the fame and glory he so longs for, including engaging in mild flirtation with Hrothgar’s queen and later being seduced by Grendel’s voluptuous mother. Moreover, nearly at the end of his battle with Grendel, the monster states, “I am not the demon here. What are you?”.

Finally, the resemblance between Beowulf and Grendel is directly hinted at by none-other than Grendel’s mother who, when Beowulf arrives to her underwater lair, confronts the hero about the very nature of his being, “Beowulf: What do you know of me… Demon? / Grendel’s mother: I know that underneath your glamor you’re as much a monster as my son, Grendel.” There may not be such differences between hero and monster all together, but it is clear that because of the unholy union (between a she-fiend and Hrothgar) he was born from, Grendel becomes an outcast, cursed by grotesque looks that set him apart from Humankind for, in the end, he is neither man nor monster.

IV – Conclusion

After studying the main points of both the poem and its different adaptations, it is clear that a great change has occurred in what comes to depicting Grendel, one of the most famous monsters of English literature. In the anonymous medieval work Beowulf, it is undeniable that the horrific Grendel is portrayed as a devilish creature; he is a fiend from hell; a God accursed brute; a heathen and a cannibal – all traits that confirm his condition as a “monster”. However, after a careful analysis it has become clear that Grendel also possesses human-like characteristics: physically, he is man-shaped and, on an emotional level, he can feel hate, fear and lonesomeness.

Most recently, screen adaptations have followed two very different traditions when it comes to representing Beowulf’s first opponent. On the one hand, movies portray Grendel as an embodiment of the terror lurking in the night, highlighting his darkest features and often removing any remainder of his humanity, such as in Beowulf (1998) in which Grendel does not bare any resemblance to a human form, but is only a “hater of happiness”. On the other hand, movies also cast Grendel as an unfortunate, castaway creature that murders and ravages Hrothgar’s mead-hall because he was provoked into doing so, like in Beowulf and Grendel (2005) and Beowulf (2007). Interestingly, in both Gunnarsson’s and Zemeckis’ vision of the poem, Grendel takes on the role of the victim; according to the first he strikes to avenge his father’s gruesome murder whereas in the second, the monster’s raids are a direct result of his abnormal sensitivity to loud sounds so, in fact, he attacks because the pain caused by the voices in Heorot is too great for him to bare. According to Stephen Asma, the 20th and 21st century public has started to face new kinds of monsters and heroes; it is almost as if the roles are inversed and one can feel empathy towards the monsters and disgust for the hero. The author also claims these two film directors (Gunnarsson and Zemeckis) restructure how Grendel’s actions can be perceived, making him a monster because he is cast out of human society and not cast out because he is a monster.

Zemeckis’s film follows Gunnarson’s 2005 version in casting Grendel as the sad, misunderstood outcast rather than the evil monster we find in the original, “In the original Beowulf, the monsters are outcasts because they are bad, just as Cain, but in the new liberal Beowulf the monsters are bad because they are outcasts. And while the monsters are being humanized in the new versions, the hero is being dehumanized” (Asma, 2009: 101).

The elderly Beowulf in Beowulf (2007) acknowledges that “We men are the monsters now.” Without a doubt, nowadays, just because someone looks like a monster does not mean (s)he is one or vice-versa, which means there was a crucial change in society’s view of monstrosity. It can be said that our notion of monster is very different from the one held by the medieval Man – today, only aliens or creatures from other planets can fulfill the space left open by medieval monsters. Simultaneously, audiences around the world are faced with a continuous questioning on the heroic character of the so-called “heroes” and of Man’s own humanity. Therefore, doubts like “where do monsters come from?”, “what is monstrous behavior?”, “can Mankind be the one responsible for the creation of monsters?” etc., start being echoed into the big screen effectively reinventing the role traditionally played by creatures such as Grendel. The notion of hero was also modified: during the Middle Ages there were strict codes of nobility that a hero had to follow – courage, loyalty, and honor. Now, the hero can be anyone as long as (s)he is brave enough to fight and free others from distress.

Bibliography

ASMA Stephen T. (2009) – On Monsters. An Unnatural History of Our Worst Fears, Oxford/New York, Oxford University Press, ISBN-13: 978-0195336160, 368 pp.

Beowulf. (1999). Traduzido por Kevin Crossley-Holland. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN-13: 019-2833200, 128 pp.

---. (2001). Traduzido por Seamus Heaney. New York: WW Norton&Co, ISBN-13: 978-0393320978, 220 pp.

GIL José. (2006) – Monstros. Tradução de José Luís Luna, Lisboa, Portugal, Relógio d’Água, ISBN-13: 972-708-890-2, 161 pp.

NIETZSCHE Friedrich. (1998) – Beyond Good and Evil. Traduzido por Marion Faber. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN-13: 019-2832638, 198 pp.

ORCHARD Andy. (2003) – Pride and Prodigies. Studies in the Monsters of the Beowulf-Manuscript, 1st ed., Toronto, Canada, University of Toronto Press Incorporated, ISBN-13: 978-0802085832, 360 pp.

---. (2004) – A Critical Companion to Beowulf, Cambridge, UK, D.S. Brewer, ISBN-13: 978-1843840299, 416 pp.

TOLKIEN J.R.R. (1958) – Beowulf: the Monsters and the Critics. London, UK, Oxford University Press, 53 pp.

VARANDAS Angélica – “O Dragão: (Pre)Figurações de Combate em Beowulf”: Flor, João Almeida e Correia, Mª Helena Paiva, ed., Anglo-Saxónica 10/11. Lisboa, Portugal, Edições Colibri, 1999, 311-336, ISBN: 0873 - 0628.

Websites

“Beowulf in Hypertext”

http://www.humanities.mcmaster.ca/~beowulf/main.html (acedido 23/03/2011).

DESMOND Marilynn – “Beowulf: The Monsters and The Tradition”, in Oral Tradition Journal, 7/2, 1992. 258-283.

http://journal.oraltradition.org/files/articles/7ii/5_desmond.pdf (acedido a 5/04/2011).

JOKINEN Anniina – “Heroes of the Middle Ages”, in Luminarium, December 2, 1996.

http://www.luminarium.org/medlit/medheroes.htm (acedido a 5/04/2011).

SLADE Benjamin (ed) – “Beowulf on Steorarume (Beowulf in Cyberspace)”

http://www.heorot.dk/beowulf-on-steorarume_front-page.html (acedido a 23/03/2011).

Films

Beowulf (1998), Dir. Yuri Kulakov, USA/UK.

Beowulf and Grendel (2005), Dir. Sturla Gunnarsson, Canada/Iceland/UK.

Beowulf (2007), Dir. Robert Zemeckis, USA.

Notes

1“The world of monsters is neither barbarism nor hell, it does not oppose itself to one or another particular representation, but to the world as an image of a place where the rational and mortal Man lives and of which he is its safest guardian.” All the translations of José Gil’s work Monstros (Monsters) will be provided by the authors, Brito, Andreia and Martins, Ana Rita.

2“Probably, Mankind only produces monsters for one reason: to think about their own humanity.”

3In The Odyssey, by Homer, Ulysses fights with the Cyclops Polyphemus, son of the god of sea Poseidon, and, because he blinds Polyphemus, the hero is placed under a curse that will make him wander in the open sea for ten years.

4Behemoth is a mythological creature mentioned along Leviathan, a sea monster, in the Book of Job. Many scholars have understood both creatures as monsters of enormous strength and bringers of chaos. Leviathan is said to be one of seven princes of hell and, some suppose, its guardian, since it was(is) believed that one can enter hell via a passage-way shaped as the opened mouth of a monster, literally a “hellmouth”.

5In Indo-European, the word “hero” had the primary sense of “protector” or “helper”. Some authors claim that the original hero was probably based on the king who died for his people or the warrior that defeated the tribe’s enemy(ies). In fact, the idea of the hero as a savior nearly dominates early medieval epics.

In epic literature, heroes are men who excel through their valor, prowess, loyalty, generosity and honor, usually fighting for their tribe or nation. The epic hero is aware of his own mortality, but does not shrink from battle or death on account of it, quite on the contrary for, because he lives in a “shame culture” in which a man’s good name and/or honor is his most cherished possession, the hero must face his opponents or live in dishonor. In Beowulf, when the Geatish champion goes to fight the dragon, he knows he is most likely to die, but accepts his fate (or “wyrd”) without bowing to it and, thus, overcomes it. The chivalric hero, that succeeded the epic champion, had similar virtues, but he also had to know temperance and be courteous. Furthermore, the chivalric hero leaves his king’s or lord’s court in search of an adventure through which he can prove himself; he is no longer (necessarily) fighting for his people or land, but in defense of an ideal, such as Sir Gawain in the anonymous poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.

6Over the 20th century, another view of the monster was developed: future monsters that are often portrayed as cyborgs or robots. In fact, current advances in robotics have led many to envision a time when a race of artificial beings will rise up, fight, and overthrow their human makers. Films such as The Terminator (Dir. James Cameron, 1984) or The Matrix (Dir. Andy Wachowski and Lana Wachowski, 1999) have explored the fear people have of losing control of something they created. Furthermore, technological development has brought up questions as to whether or not technology can dehumanize us and, at the same time, has also helped develop the fear of encountering or being invaded by extraterrestrial monsters that may seek to destroy Humankind, a phobia portrayed in films like Alien (Dir. Ridley Scott, 1979) and Predator (Dir. John McTiernan, 1987). Space has indeed become to modern audiences what foreign lands were to the medieval Man – it is a place that causes anguish and curiosity, but above all feeds our collective imagination. Finally, these space monsters are somehow built up from the Middle Ages for, when compared to humans, they have a very different anatomy, just as medieval giants, freaks, etc., were very different from Man.

7This kind of monster has been very prolific in American TV series, like Criminal Minds created by Jeff Davies for CBS (2005-present) or Dexter developed by James Manos, Jr. for Showtime (2006-present). In addition, films such as The Silence of the Lambs (Dir. Jonathan Demme, 1991), Hannibal (Dir. Ridley Scott, 2001), and so on have depicted psychopath serial killers who can quite easily fit into conventional society.

8Now in the British Library, London, Beowulf is contained in a manuscript, Cotton Vitellius A. xv, and currently has four other texts, The Passion of St. Christopher, The Wonders of the East, The Letter of Alexander to Aristotle and Judith. While the first and last (The Passion of St. Christopher and Judith) are both predominantly religious, the remaining three are secular in content.

9The dragon is present in nearly all mythologies around the world, but has different meanings, especially in the Eastern and Western cultures. A mythical creature, the dragon in Western culture was often seen under a negative light, particularly after Christianity spread throughout Europe. Dragons were regarded as malevolent due to a growing blend between the Greek word “drakon” and the Latin “draco” which could mean “serpent” or “dragon”. In addition, the dragon also became associated to Leviathan and the Apocalypse. A symbol of evil and the image of the Devil, the dragon is related to fire but its primordial element is water, for dragons are generally said to live in underground caves surrounded by waterfalls or lakes, where they hide and guard priceless treasures – a role fulfilled by Beowulf’s dragon.

10Hereafter the term “line” will be used when talking about Heaney’s translation to Modern English and the term “verse” when referring to the Old English poem.

11The Old English text used is the one in Seamus Heaney’s 2001 bilingual edition as are all the translations of the poem presented throughout this paper.

12According to biblical accounts, Cain murdered his brother, Abel, out of jealousy because of God’s favor towards his sibling. As a result, not only was Cain cursed by God to forever wander the land, but so were all his descendants. The Lord’s punishment also determined that Cain would be the source of all bad seeds – trolls, elves and every kind of monster.

13During the Middle Ages, three options were preferred by Christians to explain monstrous genealogy: a) monsters descended from Ham (Noah’s cursed son); b) they could be directly connected to Adam; or c) these creatures were the remaining of pre-Adamite races.

14For a better understanding the Old English language, the literal translation followed by the Old English word and then Heaney’s version were added to some words.

15“There is an entire tradition extending until the 18th century which links monstrous births with the mother’s inner rottenness. A direct link between monstrous births, the female embryo’s licentiousness and its first visceral nutriment is made and can be summarized as follows: perverseness is one of the reasons why monsters exist, adding a metaphorical burden, like “a dirty morale”, to the mother’s “rotten feelings” which will feed the embryo. That is what causes monstrous births.”

16Among the many screen adaptations, one can count: Grendel Grendel Grendel (1981) by Alexander Stitt; The 13th Warrior (1999) of John McTiernan; Beowulf (1999), directed by Graham Baker; Beowulf: Prince of the Geats (2007) by Scott Wegener; Outlander (2008) directed by Howard McCain.

17Several well-known actors lent their voices to this animation picture, Derek Jacobi voices the narrator while Joseph Fiennes does Beowulf and Michael Sheen Wiglaf.

18The movie Beowulf and Grendel has actor Ingvar E. Sigurdsson playing Grendel, Gerard Butler as Beowulf, Stellan Skarsgard portraying Hrothgar and Sarah Polley in the role of Selma, the witch.

19Selma is one of the new characters inserted into Sturla Gunnarsson’s version of the poem. In the film, she loses her family while a young girl and is turned into the village’s prostitute, becoming the victim of several of Hrothgar’s men violence as well as of the king himself. Selma is also shown to have supernatural abilities and is, hence, also treated as a witch. By the end of the film, she becomes involved with Beowulf and is revealed to be the mother of Grendel’s son.

20Near the movie’s ending, Beowulf and his men find Grendel’s cave where one of the warriors, Hondscioh, spits and smashes Grendel’s father’s skull, preserved since he was a child. Such action will bring about the troll’s thirst for revenge and, eventually, lead to Hondscioh’s death.

21Zemeckis’ film is the only one of the three selected adaptations that was shot in 3D. Beowulf (2007) has Ray Winstone playing Beowulf, Crispin Glover as Grendel, Anthony Hopkins portraying Hrothgar and Angelina Jolie depicting Grendel’s mother.

Andreia Brito

Andreia Brito has a degree in Modern Language and Literature (English Studies) from the Faculty of Letters, University of Lisbon (FLUL) where she has successfully completed her Master’s Degree in Translation. Currently Andreia is teaching English to children from the 1st grade to the 9th grade. She is also planning her PHD in Medieval English Literature.

Ana Rita Martins

Ana Rita Martins has a degree in Modern Language and Literature (English Studies) from the Faculty of Letters, University of Lisbon (FLUL) where she has also successfully completed her Master’s Degree in English Literature. Currently Ana Rita is doing her PhD in English Culture and Literature and works as an English lecturer at FLUL and as a proofreader of scientific articles at INOV-INESC Inovação research center, Instituto Superior Técnico.