THE PLEASURE OF REFLEXIVITY AND IDENTIFICATION

Kim-mui E. Elaine Chan

Abstract

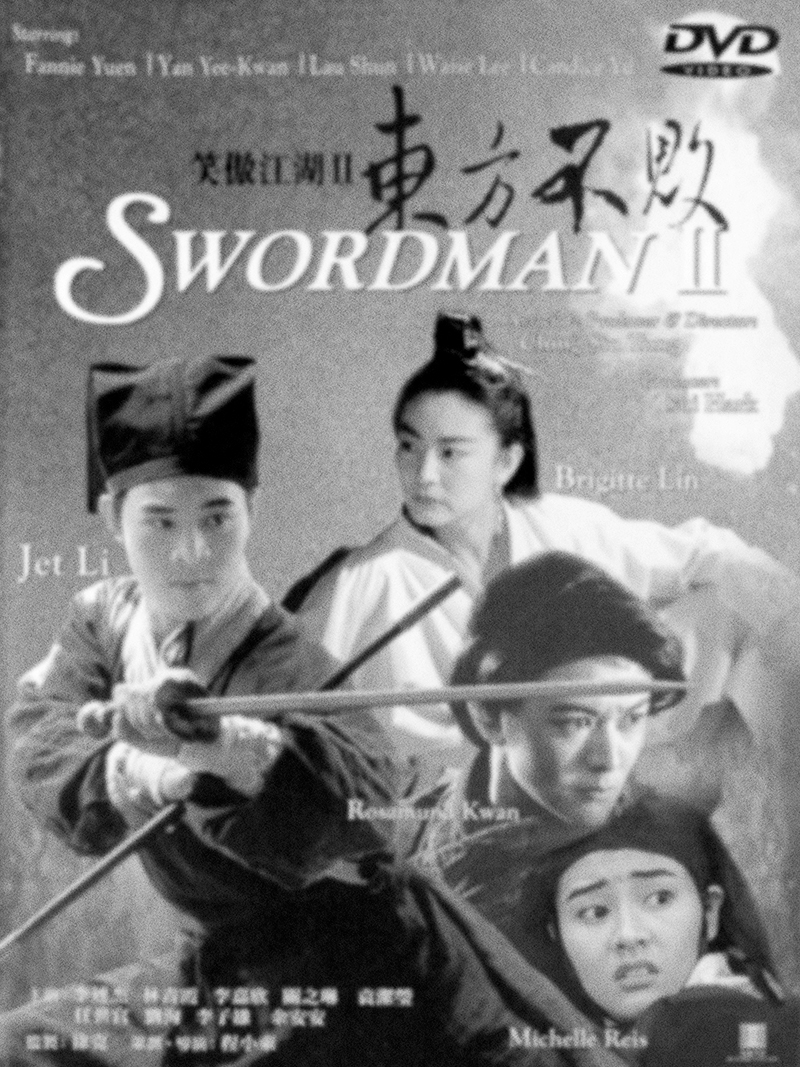

A Hongkong-Taiwanese artist’s persona of a transvestite-transsexual martial arts hero in Swordsman II: The East is Red, is the first of its kind that subverts the mechanism of abjection within the martial arts generic convention. Casting a famous female artist, Chin-Hsia Lin, for a male role who later transforms himself into a ‘femme fatale’, the film problematizes the corporeal relationship between the gender-specific bodies of the effeminate protagonist and other characters. At different points of the film, the malleable performativity of this artist, substantiated by an act of ‘cross-dressing’ diegetically, gives rise to some ambiguous gender mis-recognition. While the film invokes a sense of masculinity crisis, it also evokes genre expectation of film noir. Hence, it destabilizes, differs and defers an interpretation of crises—personal, social, political and cultural—by soliciting self-conscious rereading of suffering, evil, fate, chance and fortune. The Derridean concept of différance and the Jamesian term of pastiche help explain the film practice. It can be seen that such a unique practice emancipates the audience for a new comprehension of identity and crisis, and gives pleasure of reflexivity.

A Hongkong-Taiwanese artist’s persona of a transvestite-transsexual martial arts hero in Swordsman II: The East is Red, is the first of its kind that subverts the mechanism of abjection within the martial arts generic convention. The film is an adaptation of Xiao-ao Jiang-hu, a popular Chinese novel. Additional to the original story is a ‘homophobic’ description of same-sex desire. The screen adaptation turns around the process of abjecting into a cinematic pleasure which constitutes a process of reflexive rereading of the cinematic representation. Key to the phenomenon is a film’s strategy that sets the spectators free from the conventional ideological identification with the protagonists. This is achieved by perplexing the cultural intelligibility of the persona. Casting a famous female artist, Chin-Hsia Lin, for a male role to be transformed into a femme fatale-like character. The film, therefore, problematizes the corporeal relationship between the gender-specific bodies of Lin’s role as a male swordsman and other characters. This essay looks at Chin-hsia Lin’s persona as an aspect of discourse, through which the film enjoys a capacity to represent a good body as being abject, and the abject as good. The following discussion reveals how the film exposes the spectators to the dynamic forces respectively embodied in Lin’s body as a male martial arts hero in film and a female artist by nature. Lin’s versatile performance evokes critical questions about the cinematic and the symbolic identity of the body. The inter-diegetic (both diegetic and extra-diegetic) interpretation enhanced by Lin’s transgender performance also allows the film to problematize the convention of narrative cinema. Blurring the socio-sexual boundary of gender representation, the film destabilizes the spectator-subject’s identification with the Invincible East. This essay will describe and analyze the ‘performativity’ of Lin which problematizes and subverts gender identification.

Chin-hsia Lin, famous actress well-known across China, Taiwan and Chinese communities in the world, plays the male role of a sinister swordsman called the Invincible East in Swordsman II. The story of Swordsman II is fictitiously set in the Ming Dynasty of China where Chinese martial arts are practiced not only for self-defense but also for fulfillment of an ambition to control the whole country. In a period of political instability, the chief eunuch betrays the puppet emperor and allies himself with the Sun Moon Sect, an ethnic minority group. At that time, a rebellious male leader known as the Invincible East has taken over the Sect after a power struggle. Hoping to dominate the world alone himself, the Invincible East steals a mythical book of Kwai and successfully acquires a type of sinister kung fu mentioned in the book. Striving to excel in martial arts, the Invincible East also plans to gain power over the chief eunuch in his quest for control of the entire country. Practicing the kung fu, the Invincible East is becoming effeminate due to the fact that castration is required in the practice.

One day Ling, a peace-loving martial-arts hero, happens upon the Invincible East by a lake while the Invincible East is trying out his power of kung fu secretly. During the brief encounter, Ling is very attracted to the Invincible East without noticing that he is indeed a male. They befriend each other and later fall in love. Subsequently, the Invincible East wants to deceive Ling into thinking that he is a woman. Another impromptu visit by Ling on an evening results in the establishment of deeper emotional and romantic feelings between the two. In order to continue the ruse and entertain thoughts of their emotional and physical bond, the Invincible East persuades his wife to cover for him and have sex with Ling in a dark environment hiding his true identity. Desiring Ling, the Invincible East finally gives up his martial arts career. Cross-dressed as a woman, he is confronted by his enemies on a mountain. The Invincible East no longer desires to rule the country but just rather to win Ling’s heart. Attempting to test Ling, the Invincible East threatens to kill Ying, a could-be girlfriend of Ling. He, therefore, jumps down a mountain cliff with Ying hoping that Ling will rescue him rather than Ying. When Ling quickly reaches out for Ying’s vulnerable body, the Invincible East is broken-hearted. In the end, he decides to withdraw both from the power game and love triangle, and he disappears.

Masculine Bodies and Other Options

For the most part, Hong Kong action films usually invest in heroic images that ascribe to bodies of masculinity. Many Hong Kong masculine-macho films, for instance, aspire to ‘fit the modern Western mode of health, posture and physique’ (Turner, 1995) to nurture nationalistic sentiment (Teo, 1997), or to assert a colonial subjectivity as a cultural identity. (Lo, 1996) Alternatively, Chinese or Hong Kong martial arts film draw on the Chinese literary and philosophical traditions. In this respect Louie (Louie, 2002) and Wang (Wang, 2003) widen the scope of discussion with regard to the Chinese wen-wu (or capability of being a scholar and warrior) qualities and soft masculinity respectively. The portrayal of masculinity as ‘soft’ refers to an attribute of being kind, knowledgeable and wise. Some other scholarly works focus on the heroic persona’s cultural intelligibility by making reference to a unique Chinese operatic performative styles of sheng or wen-wu sheng. Discussion on fanchuen or cross-dressing (Li, 2003) enhances a better understanding of the conventional representation of Chinese masculinity.

Chinese film rarely characterizes male kung-fu masters in female body forms. Swordsman II is a contemporary exception. Lin’s transvestite-transsexual image is a result of Hark Tsui’s tactic to queer the conventional cinematic portrayal of masculinity. In Chinese operas, cross-dressing is, however, a convention. Without queering, the Chinese operatic convention, for example, is about assigning an actress to play a male role which is civil (wen) and/or military (wu). The artist is called fanchuan performer who takes up a role of the opposite sex. In the tradition, the cross-gender performance is never a case of gender confusion. Fanchuan performance is an aspect of the performing art which is manifest in an artist’s perfected skills to imitate and represent the behaviour of an opposite sex on stage.

Swordsman II for Queer Destabilization

Being different from a fanchuan performance, the transgender performance in Swordsman II evokes queer pleasure visually (Chow, 1991; Yau, 1996; Tan, 2000; Li, 2003). Helen Hok-sze Leung (2005) opines that the cross-gender description is queer destabilization of gendered spectatorship. In her study of Swordsman II, she looks at the issue of formation of transgender subjectivity, and speaks of ‘the conditions in which transgender subjects may emerge on screen, not as symbols but as agents of his or her specific narrative of transgender embodiment.’ She emphasizes that her understanding of the film is not about an assertion of masculinity under siege. Rather, she thinks the film offers a ‘spectacular display of transsexual femininity that has successfully eclipsed the centrality of masculine heroism in the genre.’1 The discussion below, maintains that the film does not stop at destabilizing the spectatorship but also deferring and differing cinematic, gendered and cultural identification for new comprehension. I argue that queer destabilization is a prior condition to engage reflexive self-conscious comprehension.

Leung’s theory of queer destabilization presumes that a new idea of transsexual femininity can be concretized. Nevertheless, I shall look alternatively at a type of queer destabilization that differs and defers any meaning. One of the most essential criteria for making deferral and difference possible is reinvesting classical noirish elements in the film. The generic elements include noirish cinematography, narrative structure and characterization of an enigmatic ‘femme fatale’.

Yet, the use of classical elements does not make Swordsman II a film noir. Rather, it evokes the genre expectation of a film noir and invokes a noirish sense of masculinity crisis. This tactic eventually enables the film to destabilize, differ and defer an interpretation of crises—personal, social, political and cultural.

Like any other femme fatale in a film noir, the Invincible East is sexy and dangerous. However, unlike classical film noir (Frank, 1946; Borde and Chaumeton, 1946; Schrader, 1972; Hirsch, 1981; Palmer 1986; Naremore, 1995; Muller, 1998; Durgnat, 1999; Alain Silver and James Ursini 1999; etc.), the Invincible East, in the state of being abject, is never punished. The film offers an open ending to allow imagination of the transvestite/transsexual as faithful, loving and romantic. What I hope to add on to the above Chinese film scholarship is an explanation of the film tactic that gives reflexive pleasure by engaging the audience to traverse positions of cinematic, gender and cultural identification.

The Jianghu as Emblematic of Hong Kong

As an increasing number of stories of problematized masculinity and identity crises are set against similar backgrounds of a chaotic world or city in the run up to the changeover of Hong Kong’s sovereign right, critics and scholars give evidence of a common practice gradually developed through such a recurrent portrayal. The representation of jianghu as an imaginary Chinese martial arts world (Chan, 2001) is seen as emblematic of the socio-political situation of Hong Kong. Some critics also go further to ‘re-map’ (Yue, 2000) the cinematic activities culturally.

According to Stephen Ching-kiu Chan, The jianghu is allegorical as it serves to ‘engender a critical landscape on which to map the collective experiences of success, failure, hope and despair.’2 The ‘jianghu’ portrayed in Swordsman II is chaotic and corrupt, and it appears to be noirish. Although Swordsman II does not have the American noirish rain-washed roads and dark alleyways, it has natural chiaroscuro lighting throughout the film to feature the hidden danger of the forest and the martial arts world. For instance, the film demonstrates perfect manifestation of low-key lighting. When Japanese intruders sneak in, against dark shadows, the use of strong light radiates in a distance to highlight the silhouettes of tall trees and the shadows of the ninjas (Japanese assassins). This kind of visual style is used consistently throughout the film to describe Mountain Wah as the centre-stage of a political struggle. The film assumes a process of ‘cultural imagination’ or ‘cultural mediation’3 through which the spectators are given time and space to realize that they are part of an ‘imaginary collective.’4

Noir Cinematography for Cultural Imagination

At the mountain, Ling and other martial artists prepare to retire to seclusion due to disillusionment. One day before their hermitage, these innocent swordsmen are unfortunately entangled in a power struggle involving the Invincible East, the daughter of the former leader of the Sun Moon Sect, and a group of Japanese expatriates. The conflict takes the lives of the swordsmen’s beloved horses. While they mourn, the film slowly unfolds a melancholic panoramic view of Mountain Wah against heavy clouds. Such a moody portrayal of the beautifully moon-lit mountain is harmoniously connected to a long take which reveals the hiding place of the surviving members of the Sun Moon Sect. The camera’s pan movement does not only artistically join the scenographic spaces of the two shots but it also offers an omniscient perspective into the hero’s wretched life. This is indeed what Steffan Hantke would describe as ‘a panoramic view of the noir universe’. He remarks, “…film noir mobilizes an inventory of narrative strategies, of recurring themes, and of spatial tropes, which all address the diegetic totality of the noir universe and attempt to map out…a space ‘outside’…”5

The noir cinematography is not only employed in night scenes but also in daylight. For example, in a sequence of horse riding shots, a low camera angle is used to capture the characters in silhouettes. The film does not look as misty and murky as an American film noir, however, each time the horses run off-screen over the camera, a thin layer of dust moves across the foreground to create similar visual impact. Like a film noir, with deep-focus cinematography, the film offers both a full view of the place for a detailed survey. Featuring some parts of the film set at the foreground, however, the film creates suspense to entertain the audience’s imagination of a noirish jianghu. Such a cross-diegetic cultural imagination is subtly made possible in Swordsman II, and this also applies in many other cases of reinvestment of film noir in the Hong Kong cinema of the same period.

Body and Identification

As soon as genre expectation of a film noir is created, the film nuances the visual intelligibility of Lin’s body — male swordsman and femme fatale — diegetically and extra-diegetically. The representation of Lin’s body becomes malleable. It depends on Lin’s versatile artistry and skills which incorporates the Chinese operatic style of an effeminate sheng or a feminine dan. For Richard Dyer, this type of images are analysed as ‘signs of performance,’ which include facial expression, voice, gestures, body posture, and body movement6. First, the actress cross-dresses as a man while the character is a man. Second, the character cross-dresses as a woman while the actress herself is female by nature. Third, the character turns himself into a woman while the actress is female. What is intriguing about these arrangements is that the film purposefully alienates the spectators from a preconceived idea of the male gender of the Invincible East when it also solicits identification with his ‘femme-fatale’ attribute. As a result, the spectators are enabled to assume the identity crisis of this ‘femme fatale’ character according to Lin’s transgender performance.

In the film, the actress, Lin, is assigned to play a male role as the sinister Invincible East and later the character diegetically disguises as a woman to deceive Ling. When the sinister swordsman cross-dresses, he is faking an identity and behaving in a way that he thinks Ling would desire. In the course of gender re-enactment, the film spells out how Lin qualifies the transvestite-transsexual character with some elements of a dan’s performative style. For example, in the final combat between the Invincible East and his enemies of the opposite camp that including his loved one, the Invincible East quietly anticipates how he may defend himself. While waiting, he is not doing anything but sewing. The hand gestures of pulling a thread with a needle are performed in the form of a blossoming orchid, which is typical of a dan’s performance in traditional Chinese opera. Lin’s persona, however, is not confined to a style of performance but also the performativity of a transvestite-transsexual ‘dan’. Butler differentiates performance and performativity by maintaining that ‘the former presumes a subject, but the latter contests the very notion of the subject.’7 What she means by ‘performance’ is the learned performance of a gendered behaviour that is imposed on us by the social norm of heterosexuality. By performativity, she examines the discursive practice of encoding and decoding the ‘performative’8. It can be seen that Lin’s performance is not only a representation of the learned masculine behaviours but also that of the feminine ones. The film does not only re-enact a dan style but also a cross-dressed sheng style. While the film allows Lin to incorporate all of these performative elements and traverse the roles of a sinister martial arts hero and a loving transvestite-transsexual, the film exposes the film’s ‘practice of encoding and decoding the performative’. The exigency of performativity rather than performance is conducive to a pleasure of reflexivity that the film especially offers.

In the middle of the film, there is a closet scene during Ling’s impromptu visit to the Invincible East. In the scene, the Invincible East as a male appears in low-key lighting while the impromptu visit alerts him. Waiting inside the room dimly lit by a few oil lamps, Lin’s portrayed persona is akin to that of a femme fatale. Getting ready to fight against the intruder, he does not know the person’s identity as Ling. Outside, Ling is discussing and planning with a friend strategically before he breaks in. From a lower camera position, the tight framing of the two friends in a long shot imparts a strong sense of claustrophobia. It can be seen that they occupy the foreground and their images are slightly enlarged. In low key-lighting, only half of their faces are exposed in the light while the misty background behind them is revealed vividly to create an overwhelming sense of danger. This use of the chiaroscuro effect is further enhanced as soon as the shadow of a group of fighters from the dark gradually lurks in the subdued light. Inside, also in low key lighting, the Invincible East is sitting calmly close by a paper lamp in which a moth is helplessly fluttering and dying. The silhouette of the dying insect punctuates the Invincible East’s waiting.

As the light flickers, the femme fatale-like character attacks Ling with a needle and a thread conventionally used by a woman while sewing. In a medium shot, with a tilted camera, the film reveals the body’s dangerous sexuality. In a split second, the Invincible East regrets about the attack as soon as he discovers Ling’s identity. A gust of wind blows and the Invincible East’s long hair is let down softly, his femme fatale-like image becomes obvious. When he quickly pulls back the thread out of his care for Ling, his welcoming smile depicted in the chiaroscuro lighting beckons Ling. The couple put aside their differences. Ling, however, assumes that the ‘lady’ in the room requires Ling’s protection and comfort. Intending to relieve the Invincible East from ‘fear’, Ling mistakenly takes off the Invincible East’s outer coat revealing one of his ‘sexy’ bare shoulders. The body part creates a visual conundrum because it indeed belongs to an actress.

Diegetic and Extra-diegetic Misrecognition

It is not until the middle of the film, in the closet scene, that the sexual identity of the Invincible East is entirely revealed to the spectators on screen. While the spectators overhear a conversation between the Invincible East and his wife, they are enabled by the film to confirm that Lin’s enigmatic role has been a male swordsman. Ling is not the only person who has been misled but the audience is mistaken also. Such a double misrecognition is hardly a coincidence. After disillusionment, the spectators have no choice but to reread self-consciously their own understanding of the character and their act of cinematic identification with the character. Hence, they are exposed to three levels of viewing position. First, the spectators’ omniscient point of view; second, the view both shared by the spectators and the character; and third, the view outside the narrative derived from misrecognition and disillusionment. In the last viewing position, the film allows the spectators to subject their previous interpretation to scrutiny, and thus they enjoy a non-camera centred subject position and a chance to freely traverse all the three levels of viewing positions.

Rolanda Chu also presumes that the casting of the famous actress for the male role is a tactic. In her essay, “Swordsman II and The East is Red: The ‘Hong Kong Film,’ Entertainment, and Gender,” she draws on Annette Kuhn’s usage of two concepts — the ‘view behind’ the narrative and the ‘view with’ the characters —borrowed from Tzvetan Todoro. The former refers to the spectators’ vantage point of view off the screen. Whereas the latter refers to another viewing position of the spectators, which is more or less equivalent to that of the character. Apart from these two viewing positions, she proposes to study the reason for the spectators’ active explication of the star persona and its significance. She remarks,

‘Tsui’s clever usage of Lin moves beyond the dynamic of Kuhn’s “view behind,” functioning instead as what I would term a “view outside.” The purpose here is not to see behind the garb, but to look beyond the narrative completely, in order to know it is Lin Chin-hsia, the famous Hong Kong actress.’9

The ‘view outside’ offers the spectators an opportunity to reason and resolve rationally the Invincible East’s enigmatic identity. Chu explains that this ‘view outside’ is made possible when the spectators shift to enjoy Lin’s persona as the actress they have known. She assumes that this ‘view outside,’ which results from a type of non-passionate involvement within a subject viewing position, enables the spectator-subjects to interpret the film beyond the narrative. Chu’s analysis is based on a psychoanalytical film theory of cinematic identification which is true. (Metz, 1975/1982; Baudry 1985; Cowie, 1991) I shall argue, however, she has merely dealt with a case of mistaken identity. The major problematic and most interesting issue about it is indeed related to a process of mistaken recognition of gender. She says, “…(the) spectator is deliberately set-up to misrecognize, to mistake Fong’s (the Invincible East’s) identity of gender as female, just as the Ling character does in the narrative.”10

Contrary to Chu’s statement on the mistaken identity, it is important to clarify that the film does not deceive the spectators into taking Lin’s role as feminine, nor are the spectators mistaken in exactly the same way Ling is all the time throughout the film. For instance, Lin has been overdubbed with a male voice to go with her performance as a male swordsman. In the first half of the film, the character dresses consistently in clothes that are not traditionally worn by a Chinese woman. The film provides sufficient clues to imply to the audience that the character is not an ordinary woman, but it also prevents the spectators from coining the gender performativity as either masculine or feminine. I shall critique Chu’s theory of mistaken identification as follows.

Mistaken Recognition of Gender and Its Significance

According to Chu, both the spectators and Ling are misled in the same way to decode the Invincible East’s sexual identity within the narrative. In fact, the film merely distracts the spectators from figuring out the sexual identity. However, Ling, unlike the spectators, remains ignorant of the Invincible East’s true identity throughout the film until the very end. Later in the film, Ling is even driven to believe that the Invincible East is the woman with whom he has had sex.

a) Different Positions of Identification

Chu seems to suggest that the spectators have a single perspective to resolve the enigmatic identity of Lin. The spectators indeed enjoy multiple viewing positions that are derived from a narrative schema of the film that allows them to traverse different viewing positions. The spectators are therefore able to identify with the protagonist from more than one point of view at the same time and/or different times. In the case of Swordsman II, extra-diegetic and extra-filmic view-points are evoked when the film defers, differs and contests the Invincible East’s identity as a male swordsman. Therefore, there is a possibility that the spectators — male or female — may self-consciously choose to identify with the transvestite-transsexual character who assumes for himself a female identity. This may be made possible by the above-mentioned process of mistaken recognition of gender positions. Chu’s theory does not have rooms for discussion of these possibilities, but such a discussion is important. Let me elaborate on this point below in terms of a ‘view outside’ which embraces ceaseless contestation of the established belief, convention and ways of seeing the world. The Derridean concepts of différance and the Jamesian term of pastiche help explain in this essay the strategy which emancipates the audience from the ‘view’ for new comprehension ‘outside’.

b) A ‘View Outside’

Swordsman II in ‘pastiched’ cinematic forms and contents differs and defers an understanding of the film. I shall draw on the Derridean term of ‘différance’ to explain this phenomenon. In the English version of Writing and Difference, the neologism of the term ‘différance’ is not translated due to the fact that the word has a double meaning. The Derridean term refers to something different in the form and content perceived in a space, while the perception of such a difference invokes in time a sense of deferral.11 That is to say, the Derridean term is a play on the word of both meanings of deferral and difference. Below, I shall explain why I employ the term to quality the ‘view outside’. As soon as the film ‘pastiches’ the noirish plot structure and characterization of ‘the couple on the run’ and ‘the stranger and the femme fatale’ (Desser, 2003), the film creates a ‘différance’ by providing a perspective ‘outside’ the conventional way of seeing.

To further explain the ‘view outside’, Richard Allen’s critique of Christian Metz’s assumption that character-centred identification is also spectator-centred is instrumental to my argument. Metz speaks of an act of looking as a camera-centred perception through which the spectators are is to identify with what is viewed. However, Allen argues that the spectators may not occupy the perceptual point of view of the camera. Secondly, the spectator-centred identification may deviate from the character’s point of view.12 When the film reinvests or ‘pastiches’ modern noirish elements in its portrayal of an ancient chaotic jianghu, the film gives rise to a ‘view outside’ or a play of passionate historical allusions that creates a deferred pseudohistorical depth — the displaced history of the audience’s real life or a view outside. This is what Jameson describes as the new connotation of ‘pastness’, or ‘waning of our historicity….’13 Jameson writes,

“Pastiche is, like parody, the imitation of a peculiar or unique style, the wearing of a stylistic mask, speech in a dead language: but it is a neutral practice of such mimicry, without parody’s ulterior motive, without the satirical impulse, without laughter, without that still latent feeling that there exists something normal compared to which what is being imitated is rather comic. Pastiche is blank parody, parody that has lost its sense of humor….”14

In Swordsman II, the film ‘pastiches’ or appropriates both the old forms and styles of film noir and martial arts film as a practice of mimicry, yet without any satirical intention, it offers a ‘view outside’ — an extra-filmic and extra-diegetic perspectives. Such a perspective can be acquired through traversing the emotional and physical positions of cinematic identification.

c) The Same-sex ‘Appeared’ Extra-diegetically as ‘Heterosexual’

When the film ‘pastiches’, a process of mistaken recognition of gender takes place. Thus, the film does not only encourage cinematic identification with the male sinister character but it also disrupts. The spectators are then allowed to reread the seductive feminine body of the femme-fatale character. Falling in love with a man, the Invincible East is torn between two roles as a man who wants power and a ‘woman’ who wants love. As soon as the film interpolates to denounce his same-sex desire, the spectators are, however, given visual reference to a relationship of a ‘heterosexual’ swordsmen-couple on screen because the same-sex lovers are literally played by a man (Li) and a woman (Lin) respectively indeed. The screen representation, therefore, mitigates the feeling of homophobia. The spectators may feel free to identify with Lin’s character as a faithful person passionately in love. Yet, both identification and deferral of identification are completed through and against generic conventions.

The cinematic transvestite-transsexual body, however, does not discourage the spectators from identifying with this male role of illegitimate lover. Lin’s transgender performance facilitates a self-conscious re-reading and negotiation of identity diegetically and extra-diegetically. That is to say while the film enables the audience to reread the character’s worldview, the influence of cinematic identification is also differed and deferred. At an extra-diegetic level, as a result, the narrative schema gives rise to a new interpretation of the protagonist’s dangerous sexuality. This is due to the fact that the spectators are given another chance to critique and justify the stigmatization of homosexuality.

The female persona of the transvestite-transsexual character does not visually substantiate the description of the immoral behaviour that the film seemingly claims. While most of the film characters — major and minor — levy harsh comments and moral judgment against the illicit love affair between the Invincible East and Ling as well as same-sex desire more generally, the film does not appear to be homophobic. The body is, however, one of the major extra-filmic elements, which serves to relieve the feeling of homophobia. For instance, when the film shows that the Invincible East and his wife enjoy physical intimacy, there appear two female artists caressing each other on screen. Heterosexual spectators may feel uncomfortable. They may find it easier to accept the same-sex romantic relationship between the swordsmen played by Chin-hsia Lin and Jet Li. Since the spectators may perceive the body of being abject as ‘good’, homophobia is not necessarily derived. The convoluted trajectory of representation raises an awareness of self-conscious rereading of the preconceived ideas. While the film enables the spectators to become more self-conscious, they may oscillate between various positions of cinematic identification.

Chin-hsia Lin’s persona as a transvestite-transsexual swordsman is employed in Swordsman II to differ and defer cinematic identification. Hence, a nuance of the portrayal of gender performative reality is made possible. As soon as the spectators are exposed to the protagonist’s tragedy, the film slowly engages the spectators in a process of mistaken recognition of gender by reinvesting elements of classical film noir in a Chinese martial arts film. As a result, the spectators cannot escape from rereading the film. They, therefore, contest self-consciously their former understanding of moral and identity. Drawing on the ideas of Jamesian pastiche and Derridian différance, I have revealed how the narrative schema enables manifold interpretations and critiques of the screen representation, and how it may allow extra-diegetic rereading of the contemporary ideological and socio-political issues. This reflexive process is seen as pleasurable. When cinematic identification and de-identification may take place at the same time, the film offers multiple perspectives for the audience to make new comprehension of crises — personal, social, political and cultural — diegetically and inter-diegetically. Such a unique way of giving cinematic pleasure of reflexivity is worthy of further studies.

Bibliography

Allen, Richard. 1993. “Cinema, Psychoanalysis, and the Film Spectator.” In Persistence of Vision 10.

Baudry, Jean-Louis. 1985. “Ideological Effects of the Basic Cinematographic Apparatus,” In Narrative, Apparatus, Ideology. Edited by Phillip Rosen. New York: Columbia University Press.

Borde, Raymond and Chaumeton, Etienne. 1999. “Towards a Definition of Film Noir.” In Film Noir Reader. Edited by Alain Silver and James Ursini. New York: Limelight Editions.

Butler, Judith. 1993. Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of ‘Sex’. New York and London: Routledge.

-----1996. “Gender as Performance.” In A Critical Sense: Interviews with Intellectuals. edited by Peter Osborne. England, USA, Canada: Routledge.

Chan, Stephan Ching-kiu. 2001. “Figures of Hope and the Filmic Imaginary of Jianghu in Contemporary Hong Kong Cinema.” In Cultural Studies. 15(3/4). July/Oct.

Chou, Wah-shan. 1995. Tong Zhi Lun, Hong Kong: Tongzhi Yanjiu She.

Chu, Rolanda. 1994. “Swordsman II and The East is Red: The ‘Hong Kong Film.’ Entertainment, and Gender.” In Bright Lights: Film Journal 13.

Cowie, Elizabeth. 1991. “Underworld USA: Psychoanalysis and Film Theory in the 1980s.” In Psychoanalysis and Cultural Theory: Thresholds. Edited by James Donald. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Derrida, Jacques. 1978. Writing and Difference. Translated by Alan Bass. London and New York: Routledge.

Desser, David. 2003. “Global Noir: Genre Film in the Age of Transnationalism.” In Film Genre Reader III. Edited by Barry Keith Grant. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Durgnat, Raymond. 1999. “Paint it Black: The Family Tree of the Film Noir.” In Film Noir Reader. Edited by Alain Silver and James Ursini. New York: Limelight Editions.

Frank, Nino. 1946. “Un nouveau genre policier: Láventure criminelle.” In L’Ecran Francais August.

Hantke, Steffen. 2004. “Boundary Crossing and the Construction pf [sic] Cinematic Genre: Film Noir as ‘Deferred Action’.” In Kinema 22 Fall.

Hirsch, Foster. 1981. Film Noir: The Dark Side of the Screen. New York: Da Capo Press.

Jameson, Fredric. 1983. “Postmodernism and Consumer Society.” In The Anti-Aesthetics: Essays on Postmodern Culture. Edited by Hal Foster. Seattle and Washington: Bay Press.

Li, Siu-leung. 2001, “Kung Fu: Negotiating Nationalism and Modernity.” In Cultural Studies 15(3/4).

-----2003. Cross-dressing in Chinese Opera. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Leung, Helen Hok-sze. 2005. “Unsung Heroes: Reading Transgender Subjectivities in Hong Kong, Action Cinema.” In Masculinities and Hong Kong Cinema. Edited by Laikwan Pang and Day Wong. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Lo, Kwai-Cheung. 1996. “Muscles and Subjectivity: A Short History of the Masculine Body in Hong Kong Popular Culture.” In Camera Obscura 39 Sep.

Louie, Kam. 2002. Theorising Chinese Masculinity: Society and Gender in China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

----2003. “Chinese, Japanese and Global Masculine Identities.” In Asian Masculinities: The Meaning and Practice of Manhood in China and Japan. Edited by Kam Louie and Morris Low. London and New York: RoutledgeCurzon.

Metz, Christian. 1975. “The Imaginary Signifier.” In Screen. 16:2. Or Metz, Christian. 1982. The Imaginary Signifier: Psychoanalysis and the Cinema. Translated by Celia Britton, Annwyl Williams, Ben Brewster and Alfred Guzzetti. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Muller, Eddie. 1998. Dark City: The Lost World of Film Noir. London: Titan Books.

Naremore, James. 1995-96. “American Film Noir: The History of an Idea.” In Film Quarterly. 49:2 Winter.

Palmer, Barton. 1994. Hollywood’s Dark Cinema: The American Film Noir. New York: Twayne Publishers.

Schrader, Paul. 1972. “Notes on Film Noir.” In Film Comment 8:1.

Silver, Alain and Ursini, James eds. 1999. Film Noir Reader. New York: Limelight Editions.

Tan, See-kam. 2000. “The Cross-Gender Performances of Yam Kim-Fei, or the Queer Factor in Postwar Hong Kong Cantonese Opera/Opera Films.” Journal of Homosexuality. 39:3/4.

Turner, Matthew. 1995. “Hong Kong Sixties/Nineties: Dissolving the People.” In Hong Kong Sixties: Designing Identity. Edited by Matthew Turner. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Arts Centre.

Wang, Yiyan. 2003. “Mr. Butterfly in Defunct Capital: ‘soft’ masculinity and (Mis)engendering China,” In Asian Masculinities: The Meaning and Practice of Manhood in China and Japan. Edited by Kam Louie and Morris Low. London and New York: RoutledgeCurzon,

Yau, Ching. 1996. Ling Qi Lu Zao, Hong Kong: Youth Literary Bookstore.

Yue, Audrey. 2000. “Migration-as-Transition: Pre-Post-1997 Hong Kong Culture in Clara Law’s Autumn Moon.” In Intersections. 4 September.

Endnotes

1Leung, Helen Hok-sze. 2005. “Unsung Heroes: Reading Transgender Subjectivities in Hong Kong Action Cinema.” In Masculinities and Hong Kong Cinema, edited by Laikwan Pang and Day Wong. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. (Leung 2005, 83, 90)

2Chan, Stephan Ching-kiu. 2001. “Figures of Hope and the Filmic Imaginary of Jianghu in Contemporary Hong Kong Cinema.” In Cultural Studies. 15(3/4). July/Oct. (Chan 2001,15(3/4) :490). In 2004, this article is also published in Between Home and World: A Reader in Hong Kong Cinema, edited by Esther M.K. Cheung and Yiu-wai Chu. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press. (Chan 2004, 297-330)

3Ibid., 490-491

4Ibid.

5Hantke, Steffen. 2004. “Boundary Crossing and the Construction pf [sic] Cinematic Genre: Film Noir as ‘Deferred Action’.” in Kinema 22 Fall. (Hantke 2004, 22:5-18)

6Dyer, Richard. 1979. Stars, (London: British Film Institute,), (Dyer 1979, 151)

7Butler, Judith. 1996. “Gender as Performance.” In A Critical Sense: Interviews with Intellectuals. edited by Peter Osborne. England, USA, Canada: Routledge. (Butler 1996, 112)

8Butler, Judith. 1993. Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of ‘Sex’. New York and London: Routledge. (Butler 1993, 13)

9Chu, Rolanda. 1994. “Swordsman II and The East is Red: The ‘Hong Kong Film.’ Entertainment, and Gender.” In Bright Lights: Film Journal 13. (Chu 1994, 33) Although Hark Tsui was not directing the film, his influence as an executive producer was predominant and significant.

10Ibid. 34

11Derrida, Jacques. 1978. Writing and Difference. Translated by Alan Bass. London and New York: Routledge. (Derrida 1978, xviii)

12Allen, Richard. 1993. “Cinema, Psychoanalysis, and the Film Spectator.” In Persistence of Vision 10. (Allen 1993, 15)

13Jameson, Fredric. 1991. Postmodernism, Or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. London and New York: Verso. (Jameson 1991, 21)

14Jameson, Fredric. 1983. “Postmodernism and Consumer Society.” In The Anti-Aesthetics: Essays on Postmodern Culture. edited by Hal Foster. Seattle and Washington: Bay Press. (Jameson 1983, 114)

Kim-mui E. Elaine Chan

Kim-mui E. Chan teaches film studies for an MFA programme at the Film Academy of Hong Kong Baptist University. She also taught at Lingnan University and The Chinese University of Hong Kong in the areas of film and cultural studies, and taught and developed general education programmes at The University of Hong Kong. Her book entitled Hong Kong Film Noir: Reconceptions, Reflexivity and the Glocal is scheduled to be published at the U.K. with Intellect in 20177. Her academic journals appeared in Journal of Chinese Cinemas, etc. She was also a producer-director of TV documentary, and producer-copywriter of TV commercial.