AND RHYTHMIC PATTERN IN MARIE MENKEN’S

ARABESQUE FOR KENNETH ANGER

Angela Joosse

Abstract

Through phenomenological descriptions of Arabesque for Kenneth Anger, a short experimental film by Marie Menken, this paper demonstrates how the film coheres in the midst of rhythmic tension. Menken’s embodied gestures, the segmenting mechanisms of the camera, and the enticing patterns of the Alhambra of Granada interweave to form a unique cinematic contrapuntal composition. In tension with each other, the film’s distinctive rhythms incite, evidence, and critique one another. The textures of the Alhambra make palpable Menken’s gestures as well as the camera’s intermittent motions; the camera lens makes explicit Menken’s embodied presence as well as the enticement of rhythmic pattern; Menken’s bodily movements make present the camera’s mechanical beats as well as the Alhambra’s vibrating surfaces. Within this tensile meeting, each element draws out distinctive features of the others that otherwise remain hidden or implicit. Moreover, this tensile meeting is shown to inhere in a potent and generative field of movement. The paper contributes to hermeneutically clarifying Menken’s extraordinary film as well as an embodied approach to encountering the film.

The Tensile Meeting of Body, Cinema, and Rhythmic Pattern in Marie Menken’s Arabesque for Kenneth Anger

Using an exceptionally small 16mm camera, Marie Menken shot Arabesque for Kenneth Anger in 1958 while travelling in Spain with her friend and fellow filmmaker, Kenneth Anger. As Anger explains, “she didn’t want the bigger, heavier camera. She liked this little thing that she could hold in one hand; so while she was dancing around the columns and the fountains, I would occasionally be behind the camera, guiding her, so that she wouldn’t bump into something” (Anger 2006, 40). The film’s title echoes both Anger’s description of Menken’s dancerly movements with her camera as well as Menken’s cinematic renderings of the Alhambra of Granada’s arabesques. Just four minutes in length, this film at first can appear amateurish, but as I aim to describe, upon close and repeated viewings this film begins to show itself as an intricate contrapuntal composition that inheres in movement.

My simultaneous purpose in this paper is to hermeneutically clarify both Menken’s film and the bodily approach1 I have taken up in writing about the film. That is, I work to describe the ways this film unfurls affectively, perceptually, gesturally, and conceptually. Through my descriptions I aim to demonstrate how Arabesque for Kenneth Anger presents itself as a remarkable cinematic composition through the tensions amidst Menken’s embodied gestures, the camera’s mechanisms, and the Alhambra’s enticing patterns. The film coheres in the thick of these distinctive rhythms. Furthermore, these rhythms explicate and incite each other: the textures of the Alhambra make palpable Menken’s gestures as well as the camera’s intermittent motions; the camera lens makes explicit Menken’s embodied presence as well as the enticement of rhythmic pattern; Menken’s bodily movements make present the camera’s mechanical beats as well as the Alhambra’s vibrating surfaces. Within this tensile meeting, each element draws out distinctive features of the others that otherwise remain hidden or implicit. This phenomenological study of rhythmic tension in the film opens onto consideration of movement itself, expanding beyond its definition as change of place or an animating force.

Though largely overlooked in academic writing, New York visual artist and avant-garde filmmaker, Marie Menken (1909—1970) was important to the development of experimental art in North America. Her unique camera techniques and the inclusion of quotidian details in her artwork were – and still are – particularly influential for cinema artists. Stan Brakhage, Jonas Mekas, and Andy Warhol all attested to the liberating effect that Menken had on their work. Stan Brakhage relates the importance of Menken’s first film:

In the history of cinema up to that time, Marie’s was the most free-floating hand-held camera short of newsreel catastrophe shots; and Visual Variations on Noguchi liberated a lot of independent filmmakers from the idea that had been so powerful up to then, that we have to imitate the Hollywood dolly shot, without dollies – that the smooth pan and dolly was the only acceptable thing. Marie’s free, swinging, swooping hand-held pans changed all that, for me and for the whole independent filmmaking world. (Brakhage 1989, 38)

One particularly influential aspect of Menken’s cinematic style was the way her hand-held techniques evidenced her body working in tandem with the camera.

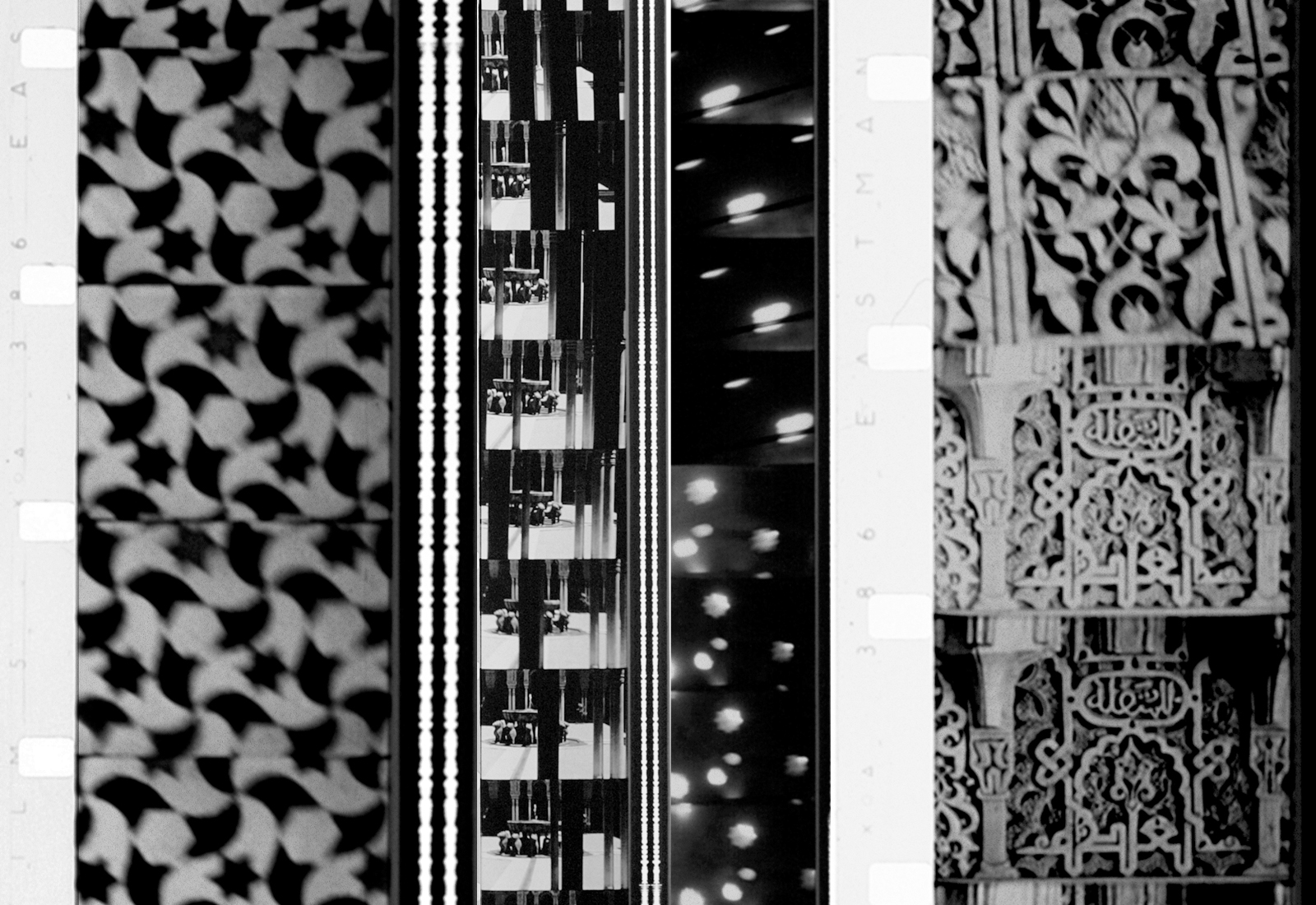

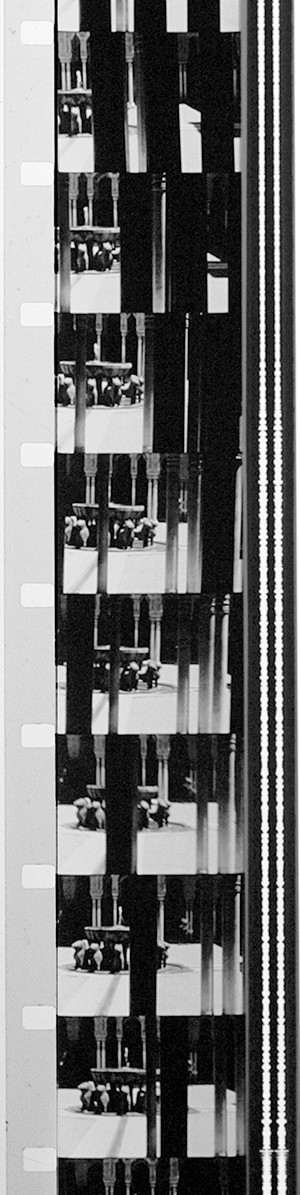

As a first entrance into the film let me describe – bodily and phenomenologically – some of its distinctive movements, which will guide us into reflection on the potency of movement itself. In many ways this film is a stepping and gliding dance through the Alhambra; we can feel the pulse of Menken’s strides and the caress of her graceful movements along the palace’s ornate arabesques, tessellations, and archways [fig. 1]. At the beginning of the film the camera hovers over a shimmering pool of water that holds the shifting reflection of flat rooftops and shining turquoise sky. This is a brief moment, a breath, before the camera traces out the edges of these courtyard rooftops in swooping gestures that follow the path of a bird in flight. The camera alights again, this time, close on a rippling and undulating surface of water. The contrast between brief hovering, hesitating, adjusting moments where the camera alights on a textured surface, and swooping, arching gestures, marks out one of the basic movements of the film. We can see this movement as one borrowed or learned from birds, a movement that stretches between the stages of flight and of alighting on surfaces and is rhythmically punctuated by the flapping of wings. Inside the palace, the camera traces out the edges of the textured archways, and then briefly slides over and alights on a mosaic detail.

Another distinctive camera movement is marked out through Menken’s use of pixilation, or shooting a single frame at a time. A cluster of single frame shots flutters around the sculpted lion beasts that encircle one of the fountains. An assemblage of frames marks out a domed ceiling’s aureole of windows. Foregrounding the segmenting motion of the shutter, these strings of single frame shots mark out visual rhythms of repeated forms which we may find helpful to describe as the feeling of running one’s fingers along a string of beads.2

The film draws its viewers in to experience many echoes between the different shots and movements. The variegated edge of the archway echoes the rippling water and the variegated edges of the courtyard rooftops. The swooping birds in flight echo curvilinear movements along the contours of the archways. The segments and repeated forms of the pixelated sequences echo the repeated geometries that make up the palace’s archways, its arabesques, and tessellations. We can see how these fragments continually overlap and develop out of one another. Slight shifts in focus and jiggling camera movements also echo the undulating reflective surfaces of water. These vibrating surfaces also seem to resonate and synchronize with the music’s textures of guitar strings, flute, and castanets. Further, the subtle shifts and hesitations found in the hovering, alighting shots in Arabesque for Kenneth Anger along with the sweeping, blending movements emphasize embodied seeing.

These movements echo the perpetual movement of the eyes, the productive mutuality of binocular vision, as well as the location of seeing within the moving, gesturing body.

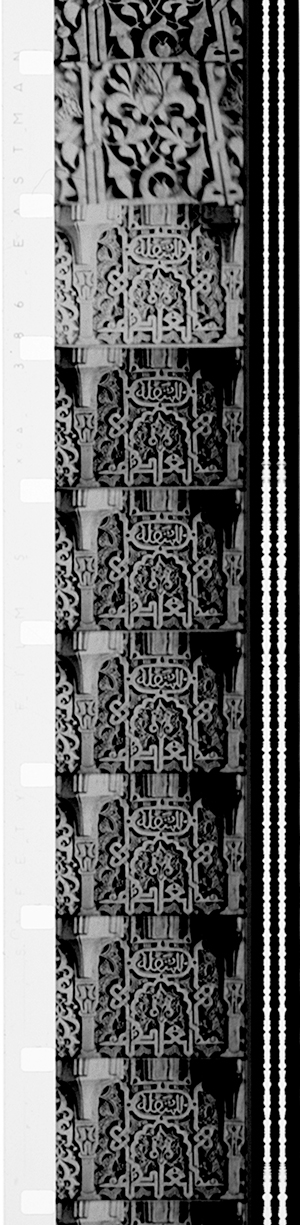

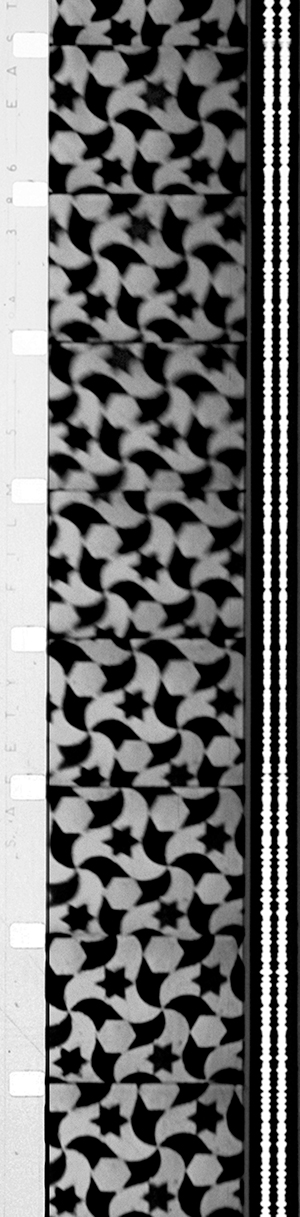

One of the striking aspects of Arabesque for Kenneth Anger is the way it contrasts perceptions in movement with alighting on detail. Certain forms, figures, and rhythms show up in movement that remain implicit or hidden within focused stillness. When the camera swings over tiled patterns, a kind of depth appears as certain shapes lift off and flow in synchronous movement like the movement of a school of fish or flock of birds. In a particularly enticing sequence, a cluster of little star or flower-shaped windows transform into what can be described as an array of dancing, shooting stars [fig. 2]. The camera pauses momentarily, showing the cluster of window lights, only to dive back into swirling and s-curved movements. Beams of light pivot in relation to these movements as these shifting points of light refract through the camera lens and spread onto the surface of the film. These movements are playful, delightful, and deeply sensuous. In the moments of alighting pause I can see more exactly, but they also hold a kind of retention of the pleasure of movement, and the pleasure is in the movement itself, like that of running one’s hand through sand or a jar of beads. Moments of arrest only heighten the joy of a continual return to movement.

It is clear from the limited critical writing on Menken’s work, that movement is integral to her cinematic style. We can hear this, for example, when Parker Tyler says that Menken’s camera “demonstrated the nervous, somewhat eccentric, rhythmic play of which the camera as itself a moving agent is possible” (Tyler 1969, 160). P. Adams Sitney’s description of what he terms Menken’s “somatic camera” offers insight into the way the jolts and quivers in her films are not merely evidence of inept or careless camerawork, but are integral to her cinematic style. These incongruities, what Sitney describes as “the awkward split-second hesitations at the beginning of shots and the tiny shifts of direction and rhythm that may first strike us as accidents” (Sitney 2008, 45), became the foundation of Menken’s “cinematic poetics” (Sitney 2008, 46). On the other hand, Melissa Ragona argues for Menken’s cinema to be understood as performative events open to chance operations, and as offering kinetic critique of the static plastic arts. Ragona states that Menken’s “handheld camera produced a frenetic vertigo on sculptural, architectural, natural, and domestic objects, while her play with animation stretched the borders of film frame and event” (Ragona 2007, 23). Further, Juan A. Suárez highlights the technological aspects of Menken’s camerawork: “She cut into reality in order to reveal intricate configurations indiscernible to the unaided eye. By stopping the camera every frame or every few frames, she disassembled motion to reassemble it again in gradual increments” (Suárez 2009, 80). From these varied descriptions of Menken’s cinematic style we can begin to ascertain the importance of movement, including bodily movement, the animation of static objects, and the mechanical motions of the camera.

It is helpful at this stage to turn to Merleau-Ponty who’s philosophy is pivotal in coming to grips with how the body itself understands phenomena like perception and movement. In Phenomenology of Perception he describes the way movement actually draws out tactile phenomena:

There are tactile phenomena, alleged tactile qualities, like roughness and smoothness, which disappear completely if the exploratory movement is eliminated. Movement and time are not only an objective condition of knowing touch, but a phenomenal component of tactile data. They bring about the pattering of tactile phenomena, just as light shows up the configuration of a visible surface. Smoothness is not a collection of similar pressures, but the way in which a surface utilizes the time occupied by our tactile exploration or modulates the movement of our hand. (Merleau-Ponty 1962, 315)

The importance of exploratory movement to tactility relates to the kind of vision that Arabesque for Kenneth Anger cinematically presents. It is a moving vision, the kind of seeing we experience while walking, one that glides over textured surfaces and is continually modulated in relation to its surroundings. Within this exploratory movement, perception draws out distinctive details. The film shows certain visual phenomena that disappear without movement; movement here is a potent component of seeing, and alighting on detail can be understood as inhering in this movement. Uniquely cinematic forms – a “school of fish,” an array of “shooting stars” – appear in the midst of Menken’s gestures, the camera’s intermittent motions, and the Alhambra’s patterns. Movement and time are not just added qualities, not just animating features of static objects, but are the very stuff of Arabesque for Kenneth Anger.

The fact that it is Merleau-Ponty’s description of the importance of movement to the intelligence of touch that resonates with Arabesque for Kenneth Anger takes on further depth as the film’s movements also take on the phenomenological presence of a tactile caress. This moving-seeing is embodied seeing and as such remains entwined with the gestures of the body as well as other modes of sense perception, particularly that of touch. There is a way in which the visual content of the film draws these surfaces into the hand, or, in which vision here becomes an extension of touch. The overlap and reversibility between seeing and touching remains prominent in the film. We see through Menken’s bodily gestures, her steps, her arching movements, her breathing, and her exploratory seeing. In this way, her camera becomes as closely aligned with touching as with seeing, and it is within movement and time that these perceptions overlap.

The film repeatedly presents sweeping-to-pausing movements over the sculpted relief patterns of the palace’s walls and pillars. These movements are akin to running one’s hand over the textured surfaces in a kind of caress. The camera pans down and across the intricately carved arabesques of the palace walls. A pan down the rippled surface of a pillar allows these undulations to pulse and vibrate along the edge of the frame line. These serpentine surfaces are so enticing and so appealing that they simultaneously draw out this tactile seeing-touching. What I am working to describe is the way that Arabesque for Kenneth Anger situates us so that we can actually perceive the kind of seeing that remains enmeshed with touch and gesture, and the way that sinuous rhythms actually draw out this kind of perception. That is, the film does not merely present tactile images, but reflects back to its viewers the fecundity of moving tactile seeing.

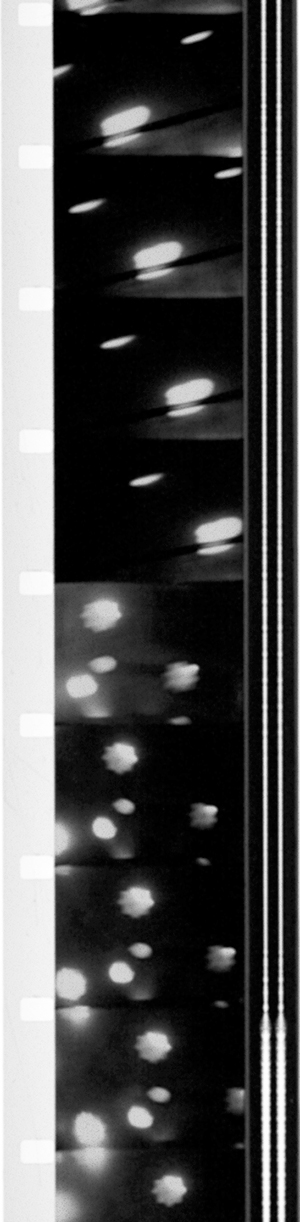

Furthermore, let me demonstrate how the film’s tensile play with space and scale actively incites, or draws out embodied perception. Grooves, recesses, and concave shapes define many of the surfaces and spaces in the film, drawing out sensuous, exploratory perception [fig. 3]. Close-up shots of clustered niches appear the perfect fit for a thumb, finger, or tongue. Titus Burckhardt describes some of these architectural configurations in his book Moorish Culture in Spain: “The Granadan craftsmen divided up entire domes into markarnas cells, into a honeycomb whose honey consisted of light itself. The magical effect of these formations consists not least in the way in which they catch the light and filter it in an exceptionally rich and satisfactory graduation of shadows, making the simple stucco more precious than onyx or jade” (Burckhardt 1972, 207). These little grooves echo the forms of the archways and curved entrance ways, inviting and drawing in; cells, ripples, and stuccoed surfaces incite sensuous perception, drawing vision outside of itself. I am using the word incitement to describe the way sensuous surroundings draw ourselves out of ourselves, or the way the details of the world captivate and engender our perceptions. The movement of incitement is a drawing out or drawing towards – the way the warmth of the sun unfolds the petals of a flower.

Caressing, swinging, stepping and hesitating camera movements draw the rippling, vacillating, vibrating surfaces into my “hand.” Simultaneously, the filigree, colour and rhythm of these surfaces and openings draw my sensing body out to meet them. Like the way a flower harkens a bee with its sensuous colour and luscious forms, so too these tactile movements and luminescent depths draw out the fullness of perception as a kind of deep attunement. I do not maintain perspectival distance from objects, but perceive myself as filling these spaces the way my tongue fills the groove of my mouth or water pools and spreads. More distant surfaces are drawn in close: I feel the ridge of the bevelled rooftop; my tongue fits into the hollows of the arabesques; my hand flows over the rhythms of the tilings. In this film, as in many of her other films, Menken draws out the deeply sensual nature of her surroundings, and one of the ways she does this is by situating seeing within embodied perception. If we try to maintain a more distanced, analytical view of the film, it can appear as a merely amateurish sketch. Moving in accord with the film, I begin to perceive space and intervals between things as thick and viscous, and in a way my “body image” is drawn into these spaces with variations of exploratory movement.

Within Arabesque for Kenneth Anger’s unique cinematic situation, viewers can perceive the overlap and distinction between cinematic imaging and embodied vision. Rhythmic pattern and textured detail are shown as particularly adept at drawing visual perception out to meet them. Both the Alhambra’s serpentine patterns and the film’s rhythms in light and colour captivate the eyes and incite embodied perception. Menken’s exploratory and playful gestures in relation to the Alhambra’s arabesques, cinematically draw out this side of perception that is continually captivated and modulated by the richness and depth of its situations.

At the same time, tensions between camera “vision” and embodied vision remain prominent in the film. Menken often moves “too quickly” for the camera to register clear images. Particularly the swinging motion of the camera over tessellations makes evident the relative speed of the camera shutter. This blurring both echoes the general and ambiguous flux of embodied or peripatetic vision moving through architected space and foregrounds an “artifact” of the meeting of frames-per-second and interwoven geometries. In a way we could think of these meetings of pattern and rhythm as moiré patterns, a phenomenon in which overlapping grids make new patterns that appear to vibrate. Moiré patterns are conventionally considered undesirable in film, video and photography, but like the inclusion of hesitating movements, these “noisy” qualities show up the way these different patterns modify each other through rhythmic tension. Furthermore, the lines and ripples of the Alhambra’s textured surfaces also vibrate along the edges of the picture frame3 as the camera continually pans and swings. These vibrational lines are also typically considered artifacts to be avoided in cinematography, but in Arabesque for Kenneth Anger these lines trace out a palpating caress of tactile seeing.

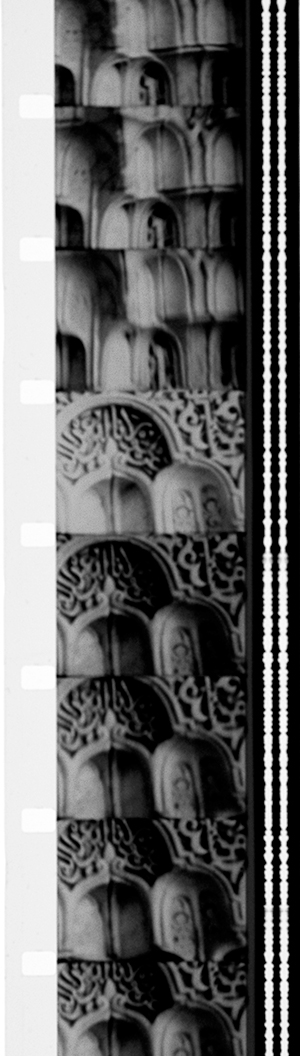

The chopping, grabbing, and intermittent freezing motions of the camera are also made explicit through the pixelated sequences. In a stroll around the outer corridor of the Court of the Lions, the pillars between the corridor where Menken walks and the interior space appear as an external shutter [fig. 4]. The pillars fragment and flicker our view of the interior patio where the twelve sculpted lions hold the fountain basin on their backs. Pulsing across the film frame, the pillars appear as an equivalent of the chopping motion of the shutter and the intermittent motion of the strip of film through the camera gate. The jumps and gaps from one frame to the next most often remain unnoticed when the camera runs at twenty-four frames-per-second, but Menken’s camera makes them palpable. Menken’s movements with the camera in relation to the Alhambra’s repeated geometries simultaneously make visible both her particular embodied gestures and the mechanisms of the camera. Through this tension we feel the artwork both as anonymously, technologically generated and as uniquely personal (style). This counterpoint appears and inheres in movement itself.

In order to help describe the importance of rhythmic tension to the film’s presence, let me turn to a particular sequence in Arabesque for Kenneth Anger in which the film enters a sliding back and forth movement over a tessellation of hexagonal shapes and dove-like shapes against white [fig. 5]. These shapes blend and appear to move in a synchronized way, like a flock of birds. As the camera begins to make more radical swooping gestures, the dove-like shapes take flight and soar. Sitney’s description also draws out the birdlike qualities of this sequence: “pushing the avian metaphor, she suggests the image of flocks of birds zigzagging in flight by rocking the camera over the field of tiles” (33).

Consider the between nature of movement, the tension-cohesion through which this “flock of birds” appears. Metaphors of flight help describe what so easily appears before us, and furthermore, they can help us see how Menken is drawing out themes of light and flight throughout the entire film. But how might this movement itself be described more fully? Within this movement, perception of depth becomes heightened. In movement these shapes blend and appear to lift off from the white background, and the tiled surface appears to become fluid, almost viscous. Not only does this movement evidence the body, Menken’s somatic presence, but also it begins to show the tensile fullness of seeing in movement.

This is not only a representation of movement, not just evidence of movement, but these forms appear in movement – were made from movement.

Here we can begin to grasp how it is crucial that Menken realized Arabesque for Kenneth Anger on film. This is not only an impression of movement, or a dynamic image, but rather, light reflecting off the tessellations making direct impressions on the celluloid surface. Menken’s hand is not visible in brush-strokes or craft, but through the tension between her movements and the mechanisms of the camera. These forms take shape amidst the tensile meeting of tessellation, Menken’s somatic gestures, and the camera’s kinetic mechanisms. These “birds” make their appearance from the midst of movement. It is in the tension between these different rhythms that Arabesque for Kenneth Anger coheres.

How might the cinema camera, with its predilection for a smooth, steady, monocular gaze be used as an instrument to reflect upon embodied vision? How does the sinuosity of bodily rhythms clash and synchronize with the precise repetitions of the camera’s mechanisms? Menken’s inclusion of jolts, rapid pans, sudden shifts in direction, abrupt cuts, and detailing along the frame lines all conflict with the basic logic of the camera as an instrument of clear representational capture. Through her embodied movements with the camera, she draws ambiguity into her cinematic imaging to bring forth a remarkable and irreducible artwork. Ambiguity generally conflicts with the representational logic of the camera, but Menken is able to introduce ambiguity into cinematic imagery to make work that continues to offer new insights and cannot be completely summarized. One of the insights Arabesque for Kenneth Anger makes palpable – in counterpoint to the “vision” of the camera – is how for embodied human perception ambiguity is the potent and productive field from which clarity emerges. As bodies we are continually moving, adjusting, and modulating our perceptions and thoughts in time, and thus even moments of profound clarity are provisional for they modulate in relation to the flux of our situations. Ambiguity, for embodied perception, then, is the sphere of endless possibility and openings rather than merely distortion or confusion.

Our study of the tensile meeting of the rhythmic patterns of Menken’s body, the camera’s mechanisms, and the Alhambra’s surfaces has led to an expanding description of movement. Movement is commonly conceived of as merely change of place or an animating force, but through Arabesque for Kenneth Anger, movement appears as a potent field from which the phenomena of texture, detail, and pattern come forth. Furthermore, inhering in movement, the different rhythms in the film make each other explicit, inciting each other, disrupting each other, bending to each other, and drawing each other out.

Bibliography

Anger, Kenneth. 2006. Interview with Scott MacDonald. In A Critical Cinema 5: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers, by Scott MacDonald, 16–54. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Brakhage, Stan. 1989. Film at Wit’s End: Eight Avant-garde Filmmakers. Kingston, N.Y.: Documentext.

Brakhage, Stan. 1994. Stan Brakhage on Marie Menken. Film Culture no. 78:1-9.

Burckhardt, Titus. 1972. Moorish Culture in Spain. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Mallin, Samuel B. 1996. Art Line Thought. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. 1962. Phenomenology of Perception. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Ragona, Melissa. 2007. “Swing and Sway: Marie Menken’s Filmic Events.” In Women’s Experimental Cinema: Critical Frameworks, edited by Robin Blaetz. Durham: Duke University Press. 20-44.

Sitney, P. A. 2008. “Marie Menken and the Somatic Camera.” In Eyes Upside Down: Visionary Filmmakers and the Heritage of Emerson. Oxford; Toronto: Oxford University Press. 21-69.

Sitney, P. A. 2002. Visionary Film: the American Avant-garde, 1943-2000.3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

Tyler, Parker. 1969. Underground Film: A Critical History. New York, NY: Grove Press.

Filmography

Arabesque for Kenneth Anger. (1958–61). By Marie Menken. USA: Gryphon Films.

Endnotes

1Here I can offer a rough outline of the Body Hermeneutic method while hopefully some of its features become more explicit in the paper. In Phenomenology of Perception Merleau-Ponty extensively works on the way the lived body understands phenomena, particularly through four distinct regions of experience: the affective-social body, the perceptual body, the motor-practical (gestural) body, and the cognitive-linguistic body. Body Hermeneutics helps further explicate and attune to these four regions of experience and open to their unique modes of experience. These four regions overlap and “translate” each other, but they also remain distinct and work according to their own “logics.” Approaching art through bodily consciousness rather than strictly cognitive or conceptual approaches can significantly expand the ways we are able to learn from artworks and what we are able to say in relation to them. The method commits to a deep respect for artworks, accepting that they situate us with and critically reflect on important questions of how we are in the world and how we make sense of our lives and communities. To date the method has been worked out most extensively in Samuel Mallin’s book Art Line Thought (1996), but recent scholars have taken up this approach to clarify questions concerning medical ethics, philosophical exegeses, the logic of technology, and feminist studies.

2As we will see, this artwork's emphasis on film as strips or strings of frames resonates with Menken's particular approach to editing. As Brakhage describes, “She would hold the strips of film in her hand and very much as she would strands of beads to be put into a collage painting” (1989, 41).

3 Sitney also notes Menken's sensitivity to the film form: “at a time when most of her contemporaries were invoking the Dionysian imagination in their invented imagery, Menken was exploring the dynamics of the edge of the screen and playing with the opposition of immanent and imposed rhythm” (2002, 160). And as Brakhage points out in his presentation of Menken's film Hurry Hurry, the rhythmic complexity of her films is best seen at the edges of the frames (1994, 8).

Angela Joosse

Angela Joosse is a Postdoctoral Fellow in the department of Art History and Communication Studies at McGill University, conducting a research project on the cinema of New York avant-garde filmmaker, Marie Menken. She completed her PhD in the Joint Program in Communication and Culture at York and Ryerson Universities. Her doctoral dissertation, Made from Movement, theorizes movement in art through phenomenologies of artworks by Michael Snow, Marie Menken, and Richard Serra.